Malware-as-a-service

Section 1. Introduction

In May 2017, a new form of ransomware called WannaCry affected more than 230,000 personal and business computers in over 150 countries. The ransomware affected organizations, such as Deutsche Bahn AG (a German railway company), NHS Scotland (the publicly funded healthcare system in Scotland), National Health Service of England, Saudi Telecom Company, and FedEx (an international courier delivery services company). The ransomware attack is now estimated to be one of the largest global security incidents in the history of the Web.

WannaCry is based on the security exploit EternalBlue developed by the U.S. National Security Agency. WannaCry was released by the hacker group The Shadow Brokers. The Shadow Brokers announced that they provide cybercriminals with the opportunity to purchase paid subscription services allowing them to access various exploits and data stolen from important organizations. The hacking group claims to have data from Russian, North Korean, Iranian, and Chinese nuclear weapons, as well as data from the Swift banking network. Thus, shortly, we may witness the increasing popularity of a new Web-based service, namely, malware-as-a-service. The purpose of this article is to examine the history of malware-as-a-service (Section 2), the ecosystem of malware-as-a-service (Section 3), and the state of the art and the future of malware-as-a-service (Section 4). Finally, we draw a conclusion (Section 5).

Become a certified reverse engineer!

Section 2. The history of malware-as-a-service

Since the appearance of the World Wide Web, hackers have been selling malware on the market of illegitimate networks, the so-called darknet. Darknet markets are websites that operate via non-standard communication protocols, such as I2P and Tor. The primary purpose of darknet markets is to facilitate transactions involving illegal products and services, e.g., unlicensed pharmaceuticals, weapons, drugs, steroids, and counterfeit currency. Such markets are also often used for purchasing or renting malware. For example, the security specialist Jon Miller argues that the malware used for conducting the cyber-attack against Sony Pictures was not custom-made. According to him, one can easily purchase similar malware on darknet markets. The attack against Sony resulted in a release of confidential data from the film studio Sony Pictures, including, but not limited to, personal information about employees of Sony Pictures and their families. Miller stressed the accessibility of malicious software by noting that "there are probably three, four, five thousand people that could do that attack today."

It is worth mentioning that darknet markets sell not only ransomware but also access to computer botnets. Computer botnets are Internet-connected devices, each of which is running one or more bots. Botnets can be used to conduct denial-of-service attacks (i.e., making machines or network resources unavailable by disrupting services), send spam, and steal personal data. According to Webroot (www.webroot.com), a botnet consisting of 1000 infected computers in the United States costs as little as USD 180. The cheapest botnet can be bought for just USD 35. Such a botnet consists of 1000 infected computers located all over the globe.

Section 3. The ecosystem of malware-as-a-service

The ecosystem of malware-as-a-service consists of three components, namely, developers of malware (Section 3.1), sellers of malware (Section 3.2), and buyers of malware (Section 3.3). Each of these three components will be examined in more detail below.

3.1 Developers of malware

Developers of malware design exploits, write malware and conduct information security research aiming to detect information security vulnerabilities. It is important to note that malware developers are not always hacking activists that act against the law. Malware developers may, for example, work as legitimate programming freelancers who complete tasks upon requests of their clients. The developers are often unaware that the results of their work will be used for malicious purposes. The motives of malware developers and disseminators include financial remuneration, intellectual challenges, vengeance against certain organizations, alleviation of boredom, and social gains. In their book "Cybercrime: The Psychology of Online Offenders," Kirwan and Power claim that malware developers may have psychological nuances and motives similar to those of people who engage in vandalism (e.g., enjoyment, aesthetics, and equity control).

3.2 Sellers of malware

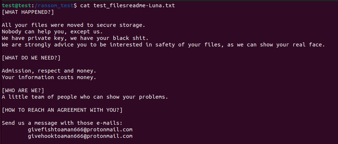

Sellers of malware usually offer their products on darknet markets and actively look for clients. Sellers normally offer their products in two categories, namely, build-it-yourself malware packages and hosted management services necessary for spreading malware. Build-it-yourself malware packages include not only malware but also detailed instructions on how to customize the malware by the needs of the person deploying the malware. For instance, anyone can buy a build-it-yourself kit that will allow him/her to deploy ransomware that mimics the functionality of CryptoLocker (a popular ransomware Trojan). The price of such a kit is just USD 100. The price is relatively low, considering that Cryptolocker may have a capability to persuade victims, including police departments, to pay the ransom. To illustrate, the Swansea, Massachusetts PD decided to respond to Crtyptolocker's demands and paid about USD 750 ransom to get their files back during an attack.

Sellers of malware also often provide hosted management services allowing their users to spread malware further. Such services may include access to botnets. The latter may spread viruses, spam, and spyware to a large number of people at once. Botnets present significant challenges for law enforcement authorities because the owners of the affected machines are usually legitimate users who are unaware of the fact that their machines are used for illicit activities. Thus, even if the authorities identify the machines constituting a botnet, they may not be able to identify the origin of the malicious code and the residence of the criminals controlling the botnet.

3.3 Buyers of malware

Buyers of malware may include three categories of people, namely, criminals planning to use the malware for malicious purposes, security researchers aiming to identify and address security vulnerabilities, and governmental officers. Needless to say, criminals buy and use malware for their own benefit. For instance, offenders may deploy ransomware to receive financial gain or create botnets to sell them to other criminals. On the other hand, security researchers may also become customers of malware producers. They can use the purchased malware for various purposes, including publishing academic articles, creating protection mechanisms to computer systems from the purchased malware, and developing updates for anti-malware programs.

Interestingly, according to Reuters, the U.S. government "has become the biggest buyer in a burgeoning gray market where hackers and security firms sell tools for breaking into computers." The U.S. government does not buy malware just to defend itself and the U.S. citizens from malware attacks. On the contrary, the government seems to use malware to infiltrate computer networks overseas. As a result, many security researchers prefer to work on malware that can be used for conducting attacks, instead of working on defense mechanisms against malware. Charlie Miller, a security researcher who previously worked for the National Security Agency, pointed out that "the only people paying are on the offensive side."

Section 4. The state of the art and the future of malware-as-a-service

At present, the business related to malware-as-a-service is in its infancy. A few providers offer their services on darknet markets. The malware sold on such markets is rarely updated, and its sellers often do not provide the purchasers with after-sale support. However, shortly, we can expect that malware-as-a-service will develop in line with the advances in legitimate software services. For example, the developers of malware-as-a-service products may provide their clients with subscription packages allowing them to get an updated version of their malware on a monthly basis. Each updated version of malware will reflect the work done by anti-virus companies during the month preceding the release of the version. Thus, the users of subscription plans will be ensured that their malware is always effective. Sellers of malware may also provide after-sale support, which can include comprehensive instructions on how to modify, deploy, and benefit from malware. We can expect that malware businesses in darknet will provide real-time after-sale support allowing their clients to fix any issues with the purchased malware quickly.

It would also not be surprising if, in the future, malware-as-a-service are offered through cloud platforms, which require their users merely to register an account and insert information, such as email addresses of the targeted persons. Afterward, the cloud platform may send malware to the designated email addresses, collect information (e.g., credit card details) without authorization, and provide the collected data to the person deploying the malware. Such malware-as-a-service cloud platforms can lead to a proliferation of malware attacks against individuals and organizations. The reason is that criminals willing to benefit from malware will no longer need to have code writing or tech expertise.

Section 5. Conclusion

This article indicated that triggered by the recent WannaCry attacks; we could expect a rapid development of a new underground economy, namely, malware-as-a-service. In this regard, TechRadar noted: "are we entering a new era of malware hell? The whole WannaCry ransomware fracas could be just the beginning of things if Shadow Brokers – the group of hackers which has previously leaked NSA tools and exploits, including the vulnerability used in WannaCry – has anything to do with it."

Although only the time will show whether we are entering a new era of malware proliferation, organizations can reduce the risks of malware by implementing flexible, well-designed, and integrated defenses. Such cyber defenses must include not only vulnerability scanners, anti-malware software, network sniffers, intrusion detection and prevention scanners, but also information security policies providing for effective coordination, flexible reporting, and knowledgeable system management. Finally, there is no perfect defense against malware. This means that organizations need to develop and implement incident response strategies aiming to mitigate the consequences of malware infections. Such strategies need to include at least six steps, namely:

- Preparation (i.e., training employees on how to respond quickly and correctly to security incidents);

- Identification (i.e., identification of security incidents);

- Containment (i.e., containment of the problem by disconnecting all affected systems and devices);

- Eradication (i.e., the affected organization investigates and addresses the origin of the incident);

- Recovery (i.e., restoring lost information and ensuring that no vulnerabilities remain); and

- Learning lessons (i.e., the affected organization learns from the incident and takes measures to avoid similar incidents in the future).

References

- Allan, D., 'Forget WannaCry: hackers promise floods of tears with fresh malware,' TechRadar, 17 May 2017. Available at http://www.techradar.com/news/forget-wannacry-hackers-promise-floods-of-tears-with-fresh-malware .

- 'Cybercriminals sell access to tens of thousands of malware-infected Russian hosts,' Webroot, 13 September 2013. Available at https://www.webroot.com/blog/2013/09/23/cybercriminals-sell-access-tens-thousands-malware-infected-russian-hosts/.

- Kirwan, G., Power, A., 'Cybercrime: The psychology of online offenders.' Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Knibbs, K., 'Anyone Can Buy the Malware Used to Hack Sony', Gizmodo, 13 April 2015. Available at http://gizmodo.com/anyone-can-buy-the-malware-used-to-hack-sony-on-the-dar-1697448923.

- 'Malware Defense for Today and the Future,' Tenable. Available at http://eqinc.com/images/white-papers/malware-defense-for-today-and-the-future-whitepaper.pdf.

- Mathews, L., '$100 malware kit lets anyone build their own CryptoLocker', Geek, 1 July 2014. Available at https://www.geek.com/apps/100-malware-kit-lets-anyone-build-their-own-cryptolocker-1581505/.

- Mathews, L., 'Even police departments are paying the Cryptolocker ransom,' Geek, 20 November 2013. Available at https://www.geek.com/apps/even-police-departments-are-paying-the-cryptolocker-ransom-1577785/.

- McClure, Stuart, Joel Scambray, and George Kurtz. 'Hacking Exposed Fifth Edition: Network Security Secrets & Solutions.' McGraw-Hill/Osborne, 2005.

- Menn, J., 'Special Report: U.S. cyberwar strategy stokes fear of blowback', Reuters, 10 May 2013. Available at http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-cyberweapons-specialreport-idUSBRE9490EL20130510.

- Palmer, D., 'Criminals in the cloud: How malware-as-a-service is becoming the tool of choice for crooks,' ZDNet, 21 April 2016. Available at http://www.zdnet.com/article/criminals-in-the-cloud-how-malware-as-a-service-is-becoming-the-tool-of-choice-for-crooks/.

-

'What is Malware-as-a-Service?', Entrust, 7 January 2014. Available at https://www.entrust.com/malware-service/.

Co-Author

"Rasa Juzenaite works as a project manager at Dimov Internet Law Consulting (www.dimov.pro), a legal consultancy based in Belgium. She has a background in digital culture with a focus on digital humanities, social media, and digitization. Currently, she is pursuing an advanced Master's degree in IP & ICT Law."

"Rasa Juzenaite works as a project manager at Dimov Internet Law Consulting (www.dimov.pro), a legal consultancy based in Belgium. She has a background in digital culture with a focus on digital humanities, social media, and digitization. Currently, she is pursuing an advanced Master's degree in IP & ICT Law."