The Device Driver Process Injection Rootkit

New SQL Injection Lab!

Skillset Labs walk you through infosec tutorials, step-by-step, with over 30 hands-on penetration testing labs available for FREE!

Part 1: Introduction and De-Obfuscating and Reversing the User-Mode Agent Dropper Part 2: Reverse Engineering the Kernel-Mode Device Driver Stealth Rootkit Part 3: Reverse Engineering the Kernel-Mode Device Driver Process Injection Rootkit

Let's now take a look at the second driver dropped by the agent. This driver allows for ZeroAccess to inject arbitrary code into the process space of other processes. Here are the hashes of this driver:

- FileSize: 8.00 KB (8192 bytes)

- MD5: 799CFC0F0F028789201A0B86F06DE38F

- SHA-1: 1023B17201063E72D41746EFF8D9447ECF109736

- No VersionInfo Available.

- No Resources Available.

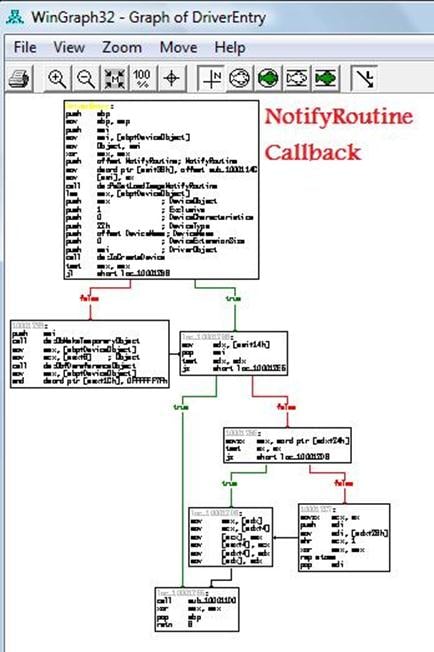

As with the first driver, in this case we see the presence of debugging symbols upon disassembly, here is a view of the call graph:

DriverEntry() essentially installs a callback. This causes the graph to misrepresent the true code execution flow, due to the fact that a NotifyRoutine represenst an indirect calling system. Keep in mind that we have a piece of code actually present that's not visible. Lets disassemble the first code block:

PsSetLoadImageNotifyRoutine registers a driver-supplied callback that is subsequently notified whenever an image is loaded for execution.

NTSTATUS PsSetLoadImageNotifyRoutine( IN PLOAD_IMAGE_NOTIFY_ROUTINE NotifyRoutine );

Parameters

NotifyRoutine

Specifies the entry point of the caller-supplied load-image callback.

After such a driver's callback has been registered, the system calls its load-image notify routine whenever an executable image is mapped into virtual memory. This occurs whether in kernel space or user space, and before the execution of the image begins.

To be able to correctly analyze this callback we need to know the prototype of a generic NotifyRoutine:

VOID

(*PLOAD_IMAGE_NOTIFY_ROUTINE) (

IN PUNICODE_STRING FullImageName,

IN HANDLE ProcessId, // where image is mapped

IN PIMAGE_INFO ImageInfo

);

The_IMAGE_INFO struct contains information about the loaded image.

This is an interesting piece of code, here we have an APC (Asynchronous Procedure Call) routine. An APC found in a rootkit is usually used to inject malicious code into victim processes.

The APC allows user programs and system components to execute code in the context of a particular thread and, therefore, within the address space of a particular process. We have two possible cases of APC usage: user-mode based (which will work if thread is placed in alertable status) and kernel-mode ones that can be of two types, regular or special.

In our case, since we are in a device driver, the APC is managed by using KeInitializeApc() and KeInsertQueueApc() functions.

VOID

KeInitializeApc (

IN PRKAPC Apc,

IN PKTHREAD Thread,

IN KAPC_ENVIRONMENT Environment,

IN PKKERNEL_ROUTINE KernelRoutine,

IN PKRUNDOWN_ROUTINE RundownRoutine OPTIONAL,

IN PKNORMAL_ROUTINE NormalRoutine OPTIONAL,

IN KPROCESSOR_MODE ApcMode,

IN PVOID NormalContext

);

And

BOOLEAN KeInsertQueueApc( PKAPC Apc, PVOID SystemArgument1, PVOID SystemArgument2,

UCHAR mode);

The APC mechanism is poorly documented and kernel APIs to use them are not public (no prototype presence in the DDK) so here we will give some more in depth explaination to well clarify how APC works.

KeInitializeApc: As the name suggests, this function is used to initialize an APC Object, from function parameters you can see that we have a KAPC struct easly uncoverable by using the method seen at beginning of the post:

kd> dt nt!_KAPC

+0x000 Type : UChar

+0x001 SpareByte0 : UChar

+0x002 Size : UChar

+0x003 SpareByte1 : UChar

+0x004 SpareLong0 : Uint4B

+0x008 Thread : Ptr32 _KTHREAD

+0x00c ApcListEntry : _LIST_ENTRY

+0x014 KernelRoutine : Ptr32

+0x018 RundownRoutine : Ptr32

+0x01c NormalRoutine : Ptr32

+0x020 NormalContext : Ptr32 Void

+0x024 SystemArgument1 : Ptr32 Void

+0x028 SystemArgument2 : Ptr32 Void

+0x02c ApcStateIndex : Char

+0x02d ApcMode : Char

+0x02e Inserted : Uchar

By watching successive function parameters you can see that the essential scope of this function is to initialize KAPC struct.

Calling KeInitializeApc does not schedule the APC yet: it just fills the members of the _KAPC, sets the Type field to a constant value (0x12) which identifies this structure as a _KAPC and the Size field to 0x30. Take a look into the ZeroAccess rootkit code ExAllocatePool, it is exactly 0x30, and is the first parameter.The KernelRoutine parameter is a pointer to a routine that will be called once APC is dispatched. NormalRoutine considered in combination with ApcMode will tell us what kind of APC is requested, so let's take a look to rootkit code:

100010E1 mov eax, [ebp+ImageInfo]

100010E7 push dword ptr [eax+4]

This means that NormalRoutine is non-zero in combination with ApcMode which is 1. We can correctly say that this is a user mode APC, which will therefore call the NormalRoutine in user mode.

Rundown Routine: This routine must reside in kernel memory and is only called when the system needs to discard the contents of the APC queues, such as when the thread exits.

Once the APC object is completely initialized, device drivers call KeInsertQueueApc to place the APC Object in the target thread's corresponding APC Queue.

Further details about APC Internals can be found HERE

Now let's study what happens in KernelRoutine:

Initially we have an IRQL Synchronization. KeGetCurrentIrql returns a KIRQL that contains the actual IRQL in which is running the current thread. Next via KfLowerIrql, we see a move to the new IRQL.ZwAllocateVirtualMemory commits and reserves a region of pages within user-mode virtual address space of the specified process. Let's take a look at the next code block:

If allocation fails, execution jumps to IRQL Restore Routine ( via KfRaiseIrql ) and then exits. Otherwise we have a memcpy that copies 0x180 bytes from sub_10001338 to allocated memory. Note that space is allocated with PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE protection, meaning that the call copied by memcpy can be executed.

Due to the fact that this memory commit has EXECUTE rights we need to analyze the block of data as if it were a block of code, because it will be executed once placed into the address space of another process. Once reached via xRefs we have to force conversion from data to code. Moving forward:

Our assumptions were correct, as you can see this is a piece of executable code. We also at 1000134E a subtle trick to prevent reverse engineering and static analysis, more opcode scission.

Now let's move our point of view from code to hex dump:

As you can see from hex dump, after the starting code (in green) we have a a string marked by red rectangle, we have already seen this string, behavior is now clear. This device driver injects the malicious DLL max++.00.x86 into victim process address space.

Next step is logically to discover what this dll does.

__The Weakness__

While this driver is made to be very stealthy, we can apply some forensic techniques to discover a weakness in the stealth technology employed by this driver. The main weakness of this driver is given by PsSetLoadImageNotifyRoutine. It essentially registers a Callback via ExAllocateCallBack, a mechanism that is very transparent and easy to find. Existing callbacks can be reveled by scanning all slots that hosts PEX_CALLBACK_FUNCTION type. To inspect these Slots we can use again KernelDetective.

ImageLoad registered Callback of an Unknown Module as should be clear, is really suspect, this is a strong evidence of rootkit infection.

Become a certified reverse engineer!

Become a certified reverse engineer!

Next up, in part 4 we can trace the Crimeware Origins by reversing the injected code!