Reverse engineering with OllyDbg

The objective of writing this paper is to explain how to crack an executable without peeping at its source code by using the OllyDbg tool. Although, there are many tools that can achieve the same objective, the beauty behind OllyDbg is that it is simple to operate and freely available. We have already done much reverse engineering of .NET applications earlier. This time, we are confronted with an application whose origin is unknown altogether. In simple terms, we are saying that we don't have the actual source code. We have only the executable version, which is a tedious task of reverse engineering.

Become a certified reverse engineer!

Essentials

The security researcher must have a rigorous knowledge of assembly programming language. It is expected that the machine is configured with the following tools:

- OllyDbg

- Assembly programming knowledge

- CFF explorer

Patching native binaries

When the source code is not provided, it is still possible to patch the corresponding software binaries in order to remove various security restrictions imposed by the vendor, as well as fixing the inherent bugs in the source code. A familiar type of restriction built into software is copy protection, which is normally forced by the software vendor in order to test the robustness of the software copy protection. In copy protection, the user is typically obliged to register the product before use. The vendor stipulates a time restriction on the beta software in order to avoid license misuse and to permit the product to run only in a reduced-functionality mode until the user registers.

Executable software

The following sample shows a way of bypassing or removing the copy protection in order to use the product without extending the trial duration or, in fact, without purchasing the full version. The copy protection mechanism often involves a process in which the software checks whether it should run and, if it should, which functionality should be allowed.

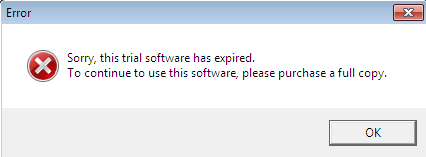

One type of copy protection common in trial or beta software allows a program to run only until a certain date. In order to explain reverse engineering, we have downloaded the beta version of software from the Internet that is operative for 30 days. As you can see, the following trial software application is expired and not working further and it shows an error message when we try to execute it.

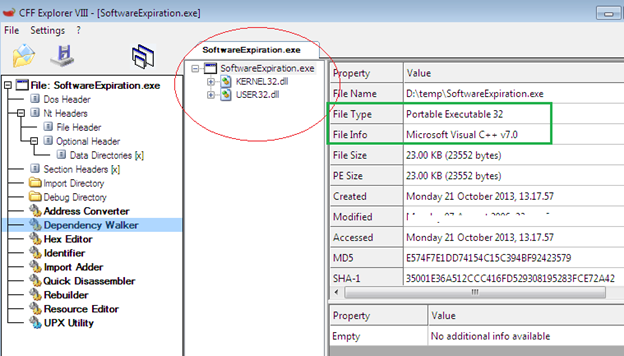

We don't know in which programming language or under which platform this software is developed, so the first task is to identify its origin. We can engage CFF explorer, which displays some significant information such as that this software is developed by using VC++ language, as shown below.

We can easily conclude that this is a native executable and it is not executing under CLR. We can't use ILDASM or Reflector in order to analyze its opcodes. This time, we have to choose some different approach to crack the native executable.

Disassembling with OllyDbg

When we attempt to load the SoftwareExpiration.exe file, it will refuse to run because the current date is past the date on which the authorized trial expired. How can we use this software despite the expiration of the trial period? The following section illustrates the steps in the context of removing the copy protection restriction:

The road map

- Load the expired program in order to understand what is happening behind the scenes.

- Debug this program with OllyDbg.

- Trace the code backward to identify the code path.

- Modify the binary to force all code paths to succeed and to never hit the trial expiration code path again.

- Test the modifications.

Such tasks can also be accomplished by a powerful tool, IDA Pro, but it is commercial and not available freely. OllyDbg is not as powerful as IDA Pro, but it is useful in some scenarios. First download OllyDbg from its official website and configure it properly on your machine. Its interface looks like this:

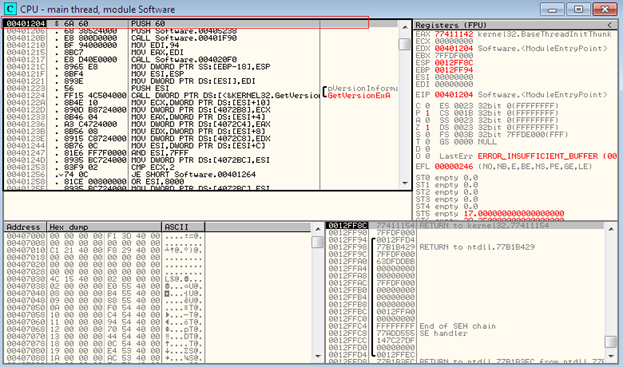

Now open the SoftwareExpiration.exe program in OllyDbg IDE from File à open menu and it will decompile that binary file. Don't be afraid of the bizarre assembly code, because all the modifications are performed in the native assembly code.

Here the red box shows the entry point instructions of the program, referred to as 00401204. The CPU main thread window displays the software code in form of assembly instructions that are executed in top-to-bottom fashion. That is why, as we stated earlier, assembly programming knowledge is necessary when reverse engineering a native executable.

Unfortunately, we don't have the actual source code, so how can we inspect the assembly code? Here the error message "Sorry, this trial software has expired" might help us to solve this problem because, with the help of this error message, we can identify the actual code path that leads to it.

While the error dialog box is still displayed, start debugging by pressing F9 or from Debug menu. Now you can find the time limit code. Next, press F12 in order to pause the code execution so that we can find the code that causes the error message to be displayed.

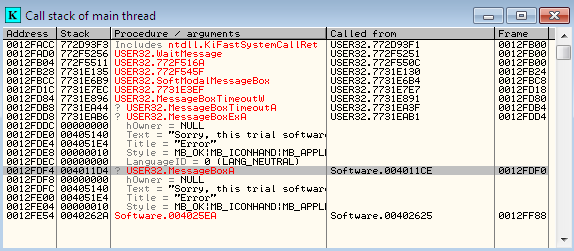

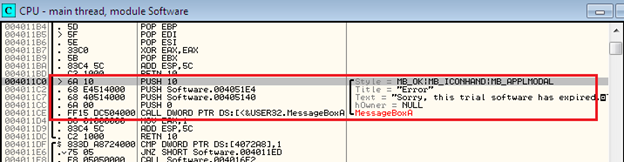

Okay. Now view the call stack by pressing the Alt+ K. Here, you can easily figure out that the trial error text is a parameter of MessageBoxA as follows:

Select the USER32.MessageBoxA near the bottom of the call stack, right click, and choose "Show call":

This shows the starting point in which the assembly call to MessageBoxA is selected. Notice that the greater symbol (>) next to some of the lines of code, which indicates that another line of code jumps to that location. Directly before the call to MessageBoxA (in red color right-pane), four parameters are pushed onto the stack. Here the PUSH 10 instruction contains the > sign, which is referenced by another line of code.

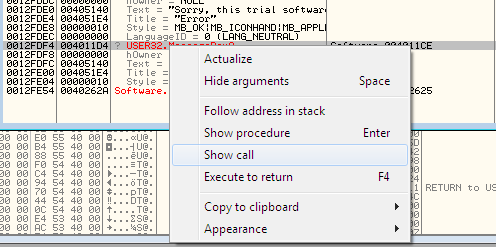

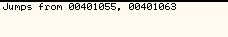

Select the PUSH 10 instruction located at 004011C0 address, the line of code that references the selected line is displayed in the text area below the top pane in the CPU windows as follows:

Select the text area code in the above figure and right click to open the shortcut menu. It allows you to easily navigate to the code that refers to a selected line of code as shown:

We have now identified the actual line of code that is responsible for producing the error message. Now it is time to do some modification to the binary code. The context menu in the previous figure shows that both 00401055 and 00401063 contains JA (jump above) to the PUSH 10 used for message box.

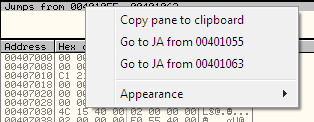

First select the Go to JA 00401055 from the context menu. You should now be on the code at location 0x00401055. Your ultimate objective is to prevent the program from hitting the error code path. This can be accomplished by changing the JA instruction to NOP (no operation), which actually does nothing. Right click the 0x00401055 instruction inside the CPU window and select "Binary" and click over Fill with NOPs as shown below:

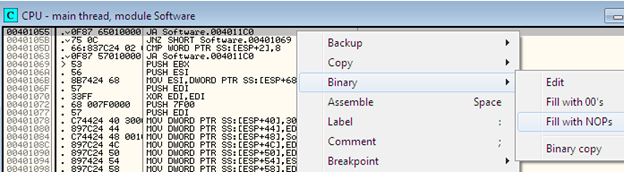

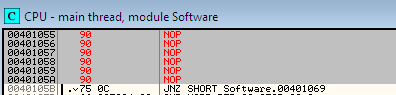

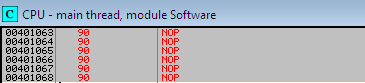

This operation fills all the corresponding instruction for 0x00401055 with NOPs:

Go back to PUSH 10 by pressing hyphen (~) and repeat the previous process for the instruction 0x00401063, as follows:

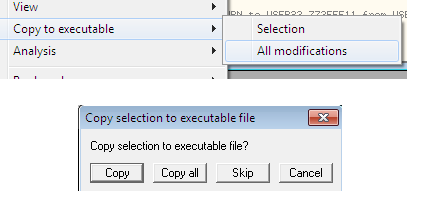

Now save the modifications by right-clicking in the CPU window, clicking Copy to Executable, and then clicking All Modifications. Then hit the Copy all button in the next dialog box, as shown below:

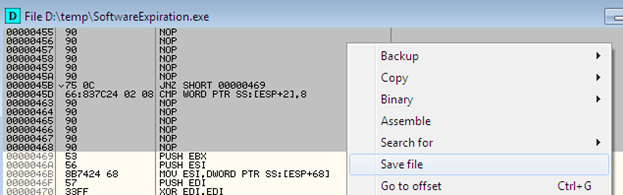

Right after hitting the "Copy all" button, a new window will appear named "SoftwareExpiration.exe." Right-click in this window and choose Save File:

Finally, save the modified or patched binary with a new name. Now load the modified program; you can see that no expiration error message is shown. We successfully defeated the expiration trial period restriction.

Final note

This article demonstrates one way to challenge the strength of the copy protection measure using OllyDbg and to identify ways to make your software more secure against unauthorized consumption. By attempting to defeat the copy protection of your application, we can learn a great deal about how robust the protection mechanism is. By doing this testing before the product becomes publically available, we can modify the code to make circumvention of copy protection more difficult before its release.

Would you like to test your skills further with a CTF challenge?