CISA is law: Now what?

The CISA cybersecurity bill passed U.S. Senate despite the fact that privacy advocates, private companies and civil liberties groups have expressed their doubts and dissent.

Hands-on threat intel training

The CISA bill

The U.S. Senate voted overwhelmingly to pass a version of the Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act (CISA), the bill requiring that private entities share information with the government about cyber-threats.

The bill, which has been debated for a long because it will authorize pervasive government monitoring of citizens, passed with a final vote of 74 to 21. Many politicians, tech giants, privacy advocates, and civil liberties groups are expressing their disappointment and consternation with the decision of the U.S .Senate.

The members of the Senate who voted for the CISA consider the bill a necessary measure against the numerous data breaches suffered by U.S. companies, including Sony Pictures, JP Morgan Chase, Anthem, and the Office of Personnel Management.

The CISA was severely criticized because it could give U.S. government agencies an advantage in collecting information about the users. The CISA establishes that data will be collected by the Department of Homeland Security and it will be shared with the FBI and NSA.

Some critics come also from exponents of government agencies: Officials of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) fear that the availability of a huge amount of threat data will increase the complexity of the analysis.

The DHS deputy secretary Alejandro Mayorkas expressed his concerns in a letter in July.

"If cyber-threat indicators are distributed among multiple agencies, rather than initially provided through one entity, the complexity for government and businesses, and the inefficiency of any information sharing program, will increase markedly. Developing a single, comprehensive picture of the range of cyber-threats faced daily will become more difficult," Mayorkas wrote.

"This will limit the ability of the DHS to connect the dots and proactively recognize emerging risks and help private and public organizations implement effective mitigations to reduce the likelihood of damaging incidents."

The privacy advocates and some members of the security industry believe that the CISA bill doesn't properly address the causes behind the long series of data breaches and the numerous cyber-attacks against U.S. entities.

We'll list the names of people who voted in favor afterwards. A vote for #CISA is a vote against the Internet. https://t.co/IctF0UYSO6

— Edward Snowden (@Snowden) 27 October 2015

"The bill is fundamentally flawed due to its broad immunity clauses, vague definitions, and aggressive spying authorities. The bill now moves to a conference committee despite its inability to address problems that caused recent highly publicized computer data breaches, like unencrypted files, poor computer architecture, un-updated servers, and employees (or contractors) clicking malware links," states the EFF disappointing as CISA Passes Senate.

The conference committee between the House of Representatives and the Senate will determine the bill's final language, but security experts and privacy defenders are skeptical about the possibility of modifying it to address the real cybersecurity problems in a correct way.

The Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act is considered the reincarnation in a new guise of the CISPA that passed the United States House of Representatives on April 18, 2013, but has been blocked by the Senate.

While the CISPA was hampered by the Obama administration due to privacy concerns, the CISA has received the consensus of the President and its staff.

"The passage of CISA reflects the misunderstanding many lawmakers have about technology and security," continues the EFF. "With security breaches like T-mobile, Target, and OPM becoming the norm, Congress knows it needs to do something about cybersecurity. It chose to do the wrong thing. EFF will continue to fight against the bill by urging the conference committee to incorporate pro-privacy language."

CISA requests sharing of "cyber-threat indicators," but doesn't address privacy issues.

Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore) is one of the opponents of the CISA bill, which he considers "flawed" and just "feel-good legislation." He warned about the abuses that could result from the application of the CISA bill.

"The fight to secure Americans' private, personal data has just begun," said Wyden. "Today's vote is simply an early, flawed step in what is sure to be a long debate over how the U.S. can best defend itself against cyber-threats."

Prior to the final vote, the principal IT companies, including Apple, DropBox, Amazon, Google, and Microsoft, also expressed their privacy concerns over the CISA and its request to share sensitive customer data to the U.S. agencies.

"We don't support the current CISA proposal. The trust of our customers means everything to us and we don't believe security should come at the expense of their privacy," said an Apple spokesperson before the final vote.

Amber Cottle, the head of global public policy and government affairs at DropBox, also joint to the opponents of the CISA bill.

"We care deeply about the privacy and security of our users and can't support CISA as currently written without more robust privacy protections. While it's important for the public and private sector to share relevant data about emerging threats, that type of collaboration should not come at the expense of users' privacy," she explained.

Cybersecurity bills in congress

CISA isn't the unique cybersecurity bill in congress; at lease other four bills addressed this very complex and much debated topic, the CTSA, the PCNA, the NCPAA and of course the CISPA.

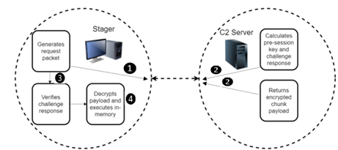

The Cyber Threat Sharing Act (S.456) (CTSA) allows private businesses to share information about cyber-threats with other organizations and government agencies. The government office that coordinates the information sharing is the National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center (NCCIC).

CTSA offers private companies liability protections to encourage cyber-threat data sharing. Differently from the CISA bill, the CTSA doesn't address defensive measures to mitigate cyber-threats, it includes a provision that limits threat data usage by government agencies instead.

Under CTSA, the U.S. Government cannot use the data shared by a company as part of a regulatory action against that company, although data collected from other sources can be used in regulatory actions.

The Protecting Cyber Networks Act (H.R.1560) was written to develop and promulgate procedures to sustain the sharing of classified and declassified cyber-threat indicators gathered by government agencies and private companies

The PCNA allows non-federal entities to share indicators or defensive measures with other non-federal entities. The bill doesn't authorize non-federal entities to share threat data with DoD agencies, including the National Security Agency (NSA).

The PCNA is quite similar to the CISA and CTSA, the bill Passed by the House on April 22.

The National Cybersecurity Protection Advancement Act (H.R.1731) (NCPAA) is very similar to the PCNA, with the great difference being that it assigns to the DHS the role of central organization for coordination of the cyber-threat data sharing. The NCPAA was passed by the House on April 23.

Cyber Intelligence Sharing and Protection Act (H.R.234) (CISPA) has been around since November 2011. The CISA is considered the evolved form of the CISPA that responds to concerns related the bill.

The latest version of CISPA distinguishes cyber-threat data from cyber-crime data. It calls for the President to designate two entities to coordinate the information sharing, one of them within the DHS for receiving cyber-threat data and one within the Department of Justice for receiving cyber-crime data.

The bill assigns to the Director of National Intelligence the task of facilitating cyber-threat data sharing between the U.S. intelligence and private organizations with a specific security clearance.

What if the Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act (CISA) becomes law?

Theoretically, if the Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act (CISA) becomes law, it would sustain the principle of sharing information between government entities and private firms. This principle is correct, but not feasible for numerous factors if the bill will not be reviewed by privacy and security experts.

Privacy and civil liberties groups, politicians, and IT giants correctly warn that the CISA would have serious privacy implications due to the unregulated sharing of customers' personal information with U.S. agencies like the NSA.

The bill was proposed by politicians who totally ignore the cybersecurity context, the threat actors and the information necessary to mitigate the exposure to cyber-attacks.

The bill doesn't add more to the threat intelligence-sharing initiative in place; today several groups have been formed to improve information sharing. Let us think, for example, of the FS-ISAC and the Cyber Threat Alliance.

The CISA totally lacks a description of how the information would be shared between two parallel worlds, the public and the private industry.

The government culture is completely different from the private industry culture in that information sharing is always hampered by a rigid classification of data and the lack of trust among different government entities worsens the situation.

The experts highlight the inability of the U.S. law enforcement and intelligence agencies to provide useful cyber-threat intelligence data to the private industry.

Some security experts speculate that one of the primary intent of the U.S. Government in pushing the CISA bill is to renew cooperation with the numerous threat intelligence experts that left the government to join private industry, which offers more opportunities for gain. A significant number of analysts have been trained by the U.S. Government and now are working for private firms.

We also cannot ignore the "Snowden effect"; the revelations made by the popular whistleblower have increased the mistrust in the private American products. The technology industry is still feeling the impact, and companies in other industries are reluctant in sharing data with the government fearing privacy violations.

Another problem when dealing with the CISA bill is the ability of the actors involved in the process in collecting the proper information on the threats. The majority of companies that were victims of a data breach were not able to identify indicators of compromise related to their systems. How can they share threat information with peers in the proper way? Does the CISA bill address this point? The response is unfortunately negative.

The experts also warn that the CISA doesn't address the underlying issues of data and infrastructure protection. Each agency that collects shared data could be the victim of a data breach; we cannot forget that and that's why it is important to define additional security requirements to ensure data privacy. The recent incident that occurred at the Office of Personnel Management demonstrates that we cannot totally trust government infrastructure and that government systems are vulnerable to cyber-attacks. The risks that government collectors of threat intelligence will become a single point of failure in case of cyber-attacks is concrete.

The CISA bill fails to enforce transparency and does not encourage organizations to share information about cyber-threats

A large number of U.S. companies also manage data of those who are not U.S. citizens and firms, if CISA bill will become law, foreign companies will become increasingly distrustful of U.S. private industry, as explained by Andrew Conway, research analyst, Cloudmark.

"Many American Internet companies have customers all over the world. Social networks, security companies, hosting companies, ISPs, webmail providers, and many other American businesses all have access to sensitive personal and corporate data worldwide. Their customers rely on them to keep that data private. In most cases, that is backed up by non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) or privacy policies. CISA says that American companies can't be sued for breaching those NDAs or privacy policies if they share information with the U.S. government. That would make it hard for those American companies to attract and keep customers in countries with strong privacy laws," said Conway to Securityweek.com.

Hands-on threat intel training

Sources

https://threatpost.com/white-house-support-for-cisa-worries-privacy-advocates/114383/

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2015/10/eff-disappointed-cisa-passes-senate

http://www.securityweek.com/industry-reactions-cisa-approval-senate-feedback-friday