Phishing Variations

Most people who spend time on the Internet have heard of Internet scams and almost everyone knows someone who got taken in by a cyber-hoax or dating scam. A classic old hoax that still does the rounds every now and then was the email that claimed that “for every person that you forward this e-mail to, Microsoft will pay you $245.00.” A portion of a sample email from the hoax-slayer website is shown below. Most people will claim they wouldn’t fall for this one.

Two year's worth of NIST-aligned training

Deliver a comprehensive security awareness program using this series' 1- or 2-year program plans.

All in all, no harm done but, since then, cyber-criminals' modus operandi has become malicious rather than mischievous. It’s not enough to recognize a hoax email (if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is); today, anyone using the Internet needs to understand what phishing is and the many variations of this scam that fraudsters use to con Internet users. Not only are there multiple variations, phishers are coming up with new ways to part you with your money faster than you can say: “I didn’t authorize that.”

What Is Phishing?

“Phishing” is not just a prank. It is the blatant theft of people’s sensitive information, e.g., passwords, email addresses, account information, social security numbers, etc., that can be used to:

- hijack individuals identities (for instance, by gaining access to their email password);

- scam contacts in a user’s personal and business network (for instance, by accessing their social networking profiles); or

- steal directly from individual’s accounts or purchase expensive resalable goods and services (for instance, by using Trojan malware on a victim’s computer).

The goal of a phisher is to trick you into giving up your sensitive information, e.g., by:

- pretending to be a legitimate organization like a bank or an authoritative organization like the IRS and requesting your personal details;

- sending you a veiled threat that you haven’t paid an account and scaring you into believing you have to take action to avoid getting into some sort of trouble; or

- appealing to some baser motive, e.g., greed, lust or nosiness.

Phishing is insidious. It may start with the theft of your email address and end with your bank account being hijacked and your email account being used to victimize anyone in your address book, including stalking, bullying, or blackmailing them. Yes, that throwaway comment about your boss having an affair with his or her secretary has enormous value for a phisher. Remember Ashley Madison? There were a number of reports of extortion and the scam was allegedly linked to at least two suicides.

Background

The first recorded reference to “phishing” was on the alt.online-service.america-online Usenet newsgroup in 1996.

"Ph" is a common alphabetic replacement hackers use for the letter "f" and the origins of that go back to Internet scamming in the 1970s, specifically “phone phreaking.”

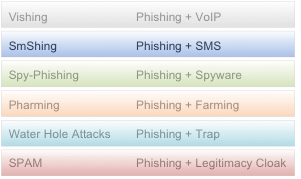

There are numerous phishing variations; in this article we’re going to look at six of them. Pay particular attention to the common threads as well as the slight variations in the attacks.

Understanding phishing and its evolution can help prevent you from becoming a victim. For instance, originally phishers deliberately used bad grammar and spelling to narrow their market of potential victims to people who would be most likely to fall for a scam, perhaps those who were not very well educated or Internet savvy (the Nigerian 419 scams used this technique very effectively). Since then, phishing networks employ phishers with specialized skills, like good grammar and spelling and efficient email marketing skills, not only expanding their market of potential victims but confusing anyone who thought they knew anything about phishing.

Phishing Variations

-

Vishing

While traditional phishing attacks most commonly use fake emails or link manipulation, vishing is when a phisher tries the same scamming techniques over the phone. There are a number of techniques used, e.g., concern that one of your accounts may be vulnerable, a threat that you have not paid a bill, an offer of a reward or prize, and posing as an employee at a legitimate company in an effort to solicit personal information from you. For instance, a victim may be offered a better deal for a service they currently subscribe to, only to discover later that not only is the deal not better, no service is actually being provided. Sound far-fetched? If you ever replied to a scam email to harangue them and threaten to go to the authorities, you made a mistake. At that point the phishers not only know that your email address was valid but they also know of at least one company you do or do not do business with. Phishing is a numbers game. Phishers have a database of information for individuals that they constantly update, slowly building a profile of potential victims, e.g., who banks with Allianz or who has a young family and could be in the market for education insurance.

The warped genius of the vishing strategy is that vishers have the gift of gab. People often say of a salesperson that he or she can sell ice to Eskimos. As individuals, vishers use different techniques but generally will try to get you to disclose information as quickly as possible, before your warning antennae have had a chance to fully prick up. They can be brusque to put you on the left foot or over-friendly, hoping to get your guard down. The most powerful weapon you have is always to phone an organization rather than have them phone you. If your bank phones to ask you to confirm your details, tell them you will phone them directly and do so.

However, in some cases, vishers may actively try to get you to phone them, perhaps sending you an email that your bill hasn’t been paid and you need to dial their call center. The vishers’ call center will operate pretty much as you expected with a consultant on hand to confirm your details and notify you that the call is being monitored for security purposes. Let’s just back track here. Confirm your details? You got it. By confirming your details, you’ve been caught in the vishers’ web.

SMiShing

SMiShing involves phishing for personal information using SMS text messages or tricking a user into downloading a Trojan horse, virus or other malware onto their cell phone or other mobile device.

SMiShing works because of the prevalence of cell phones, personally and in the work environment. Cell phones are relatively cheap and they’re pretty easy to use. They also unfortunately suffer from far more vulnerabilities than a traditional computer. For instance, on a computer you can see the actual URL for a link in an email by hovering over it. Not so with cell phones.

The main problem, however, is that people use cell phones to keep in touch with their family and friends and feel safe using their phones and less vulnerable to scams. If you do a bit of people watching, you’ll notice that people receive a message and respond virtually immediately. It is this kind of Pavlovian response that phishers often rely on and that users don’t question the veracity of the identities of senders of SMS messages.

Spy-Phishing

According to Wikipedia, spy-phishing can be defined as "crimeware" (a kind of threat that results in fraudulent financial gains). Spy-phishing capitalizes on the trend of "blended threats" and borrows techniques from both phishing and spyware. In the relatively good old days, many Internet criminals simply wanted to disrupt or annoy, and show off their coding expertise, but successful malware and spyware attacks have given rise to a much greedier hacker. It is really all about the money now.

Once upon a time a Trojan virus made your screen go black or slowed your computer down. Now spyware is designed to surf your computer for as much information as it can get and use against you, with the primary goal of parting you from your money.

Spy-phishers use traditional phishing techniques to trick users into parting with information and then typically engage a host of other techniques to download and install spyware applications in the background. Spy-phishing techniques are often the greatest threat to businesses, as they aim surreptitiously to gain control of a company’s sensitive information.

Spy-phishing in many ways is what we see in movies where hackers are able to gain access to a company’s network and surf and download sensitive files undetected.

Pharming

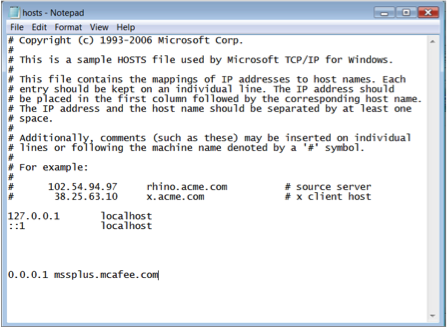

Pharming is sometimes known as “phishing without a lure”. When a user attempts to navigate to a site, their computer can determine the IP address by either consulting a local file of defined mappings—a hosts file—or by consulting a DNS server on the Internet. Pharming is usually conducted either by changing the hosts file on a victim's computer (hosts file pharming) or by exploiting a vulnerability in DNS server software (DNS poisoning).

Hosts file pharming: Attackers can place false entries in a user's hosts file either manually (rare) or by infecting it with malware that is able to modify the file. The process usually starts when the victim downloads malware that has been distributed by email or placed on a bogus website. A typically secure hosts file is often empty, so you can see if there are any unusual entries by opening the file in Notepad, but you should never rely on this manual check and always use anti-malware software. If there is a mapping for a domain name in a hosts file, your computer will not query the DNS servers for that domain, but instead read the IP address directly from the hosts file.

DNS poisoning: If the website you’re visiting is not listed in your hosts file, your computer will attempt to determine a site’s IP address by consulting a DNS server. These servers are responsible for resolving Internet names into their real IP addresses. When a DNS server is poisoned and you type the website name in your browser, you’ll be re-directed to a bogus site even if you have typed the correct web address. This type of pharming is most often used to attack you by imitating large, trusted organizations, such as banks.

Because it is very difficult to detect or avoid these attacks, occurring as they do at a very low computer level, it’s important to look for the "s" in https and the key or lock symbol at the bottom of your browser, run virus scans regularly, and check your online accounts regularly for suspicious activity. As long as the bogus addresses remain in the hosts file or on the server, you can be attacked every time you visit the malicious site so, if you’re banking every day online, the potential losses could be enormous before you notice.

Watering hole attacks

An extremely crafty variation of phishing is called the watering hole attack because, instead of directly approaching potential victims, cyber-criminals set up a trap and wait for the victims to come to them. Legitimate sites are infected with malware or phishers create their own bogus sites (often imitations of legitimate sites) and the targets are the users that frequent those sites, lured by whatever the criminals have identified as irresistible bait, of interest to a particular group.

Step 1 – victim profiling: Victims of watering hole attacks usually belong to a particular group (organization, industry, or region) targeted by phishers. In a watering hole attack, the attacker first profiles its target group using sophisticated marketing and analysis tools, including AddThis, KISSmetrics, and Google.

Step 2 – identifying preferred hangouts: The next step is for the phishers to identify (sometimes making educated guesses) which websites members of the group often use and infect one or more of them with malware. For instance, phishers could identify dating sites as the perfect watering hole for the lovelorn, often a vulnerable group.

Watering hole attacks work so well for phishers because groups of people are unlikely to stop visiting sites that are of interest to them or necessary for them to do their jobs; e.g., developer forums are an important resource for programmers and Facebook addicts need their daily fix. Facebook, Apple and Twitter have all been victims of watering hole attacks.

Candis Orr, a researcher with Stach & Liu, describes email phishing as sending random people poisoned fruit cakes and hoping someone eats one, but watering hole attacks are like poisoning a town’s water supply and just waiting for them to take a sip. The first scenario could be fruitless for the phisher, while the other is only a matter of time before the attacker hits the jackpot.

Context-aware phishing also uses this modus operandi. For instance, phishers may target people on sites like Amazon or E-Bay who bid on a particular product or type of product. Often bidders have public email addresses and are vulnerable to messages from the companies with which they have accounts. Phishers can send these users messages asking them to confirm their details using fraudulent links.

SPAM

Phishing differs from SPAM in that SPAM is usually just unsolicited junk communication and a marketing ploy, right? Think again. SPAM is the perfect environment for phishers to hide their malware and fraudulent links, or try to get you to buy something you don’t want or need. Has anyone not at some stage received an email, phone call, or SMS offering a discount on a product or service after making a legitimate purchase and giving up their phone number or email address? Examples of SPAM include messages from the magazine you never subscribed to or the news forum you’ve never heard of; the unsolicited invitation to join a network or community that can help you find a job, meet new people, or get special discounts on travel, restaurants, and other products and services. SPAM is a “numbers game”. As a marketing technique, it relies on a certain percentage, as low as a fraction of a percent, of people responding.

- SPAM is annoying at best but becomes dangerous when it’s part of a phishing attack.

- Replying to a SPAM message confirms that you are human and contactable; this is worth money to a phisher, as your information can be sold.

- Phishers use attachments to infect victims’ computers with malware or include fake links to bogus websites in the body of their messages.

- SPAM messages can include phone numbers. If you call the number, you could be connecting directly with a visher.

- If it’s not in your SPAM folder, it’s not SPAM, right? Wrong. ASCII, TXT, XLSX, RTF, PDF, and MP3 are just some of the file formats phishers use to keep switching their distribution practices and confuse your anti-spam software.

Conclusion

For small businesses as well as large corporations, it’s important that someone in the company is kept up to date with phishing trends and other types of cyber-crime. InfoSec Institute offers live online courses covering various aspects of cyber-security. You will directly learn from and interact with a live expert instructor, the same as you would if you attended a physical classroom course. These courses enable your employees to become certified cyber security specialists.

Sources Consulted

http://www.computerworld.com/article/2575094/security0/sidebar--the-origins-of-phishing.html

http://docs.apwg.org/word_phish.html

http://www.voipits.com/blog/features/learn-to-recognize-and-prevent-vishing

http://searchsecurity.techtarget.com/definition/watering-hole-attack

http://searchsecurity.techtarget.com/definition/pharming

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spy-phishing

http://www.social-engineer.org/framework/attack-vectors/smishing/

http://www.hoax-slayer.com/ms-money-giveway-hoax.html

Phishing simulations & training