Link manipulation

Link manipulation

Phishing Tools & Techniques Articles:

[clist id="1470339196766" post="36036"]

See Infosec IQ in action

Overview

Phishing scams are almost always about links. While most people are generally aware that you shouldn’t click on shady ones that come from strangers, there are a variety of clever ways in which web thieves try to cover their tracks. Here is a brief overview of some of the most common link manipulating tactics we’ve uncovered.

Hiding the URL

The most basic way phishers can disguise their links from users is by simply cloaking the true domain name in text.

One method is to simply use words instead of the actual URL, like Unsubscribe or Click to access your account. Another easy and deceptive technique is to write the hypertext so it looks like a legitimate website URL. For example: www.bankofamerica.com LOOKS like a real link to the bank. But if you click any of the above samples, you’ll see that they will take you where you didn’t expect. (Don’t worry, these all simply direct you to one of our short videos explaining that you have been “phished.”)

Another down and dirty method of hiding the actual URL is by using a shortening tool like Tinyurl or Bit.ly.

In Infosec IQ's educational portal, we have created many different phishing email templates as samples. These utilize a variety of messaging tactics (some pretend to be banks, government entities, co-workers or IT professionals) but they all use these basic URL hiding techniques because they’re tried and true and so easy that anyone can create them – or become a victim.

A phishing template from Infosec IQ’s library.

TIP: Whenever you get a questionable email or suspicious link, get in the habit of placing your mouse over it before clicking. The true URL will be revealed in a popup window.

Misspelled URLs

Another common spoofing trick is when thieves buy up variations or misspellings of popular domain names and use them to create fake websites that fool visitors – this is also referred to as typosquatting or URL hijacking. In the early days of the web, URLs were cumbersome to remember and expensive to own; as the Internet grew in popularity, domains became cheaper and more user-friendly. This made it easier for both companies and web surfers, but also opened the door to fraud.

In 2003, it was reported that hackers began to take advantage of the availability of domain names by buying up lookalikes like yahoo-billing.com and ebay-fullfillment.com. They then used these pseudo links in some of the first large-scale email phishing attacks.

Typosquatting is technically illegal; however, that hasn’t stopped these fraudsters from registering thousands of typosquatting domains in the U.S. Google was an early target and victim of such schemes. In 2005, they won the rights to googkle.com, ghoogle.com and gooigle.com, which were bought by a Russian hacker. (Ironically, Google itself has been accused of profiting from typosquatters. A 2010 study conducted by Harvard Professor Ben Edelman found that 57% of typosquat domains he investigated had some form of Google AdSense ads, which he estimated netted the company $497 million per year.)

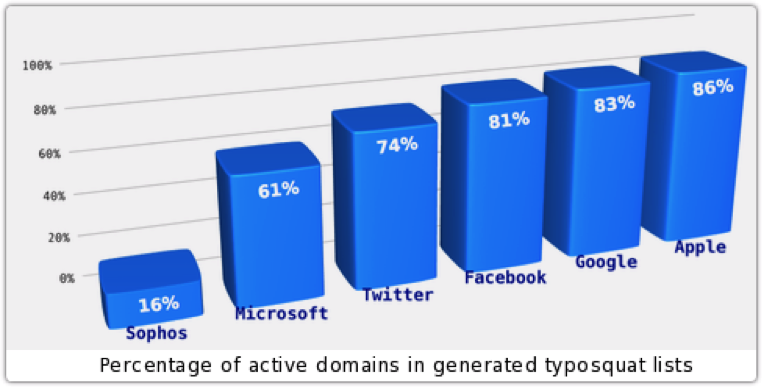

But these typosquatted websites don’t necessarily even need to be in an email link to inflict their damage; all it takes is a bit of carelessness. An investigation conducted by British IT security company Sophos, where a researcher purposely typed misspelled variations of sites like Microsoft, Apple, Google, Twitter, and Facebook into an address bar, found that 80% of these errors resulted in a redirection to a “phishy” website.

Source: https://nakedsecurity.sophos.com/typosquatting/

Many of these large companies have tried to defend themselves against typosquatting, registering as many variants on their names as they can and domain registrar GoDaddy says they comply will all court-ordered takedowns. (Google says it removes any illegal domains from search engines that they are “made aware of” and insists it doesn’t profit from ads placed on them.) Still, with so many different ways to make a spelling mistake, typosquatting can be difficult to police.

TIP: Most U.S.-based companies that are popular phishing bait have a .com address and financial institutions and others that require secure transactions have an “https://” instead of the standard “http.” Look for those identifiers before clicking any links and, when manually typing a URL, do it slowly and carefully!

IDN spoofing

A variant of typosquatting that is much harder for users to detect is called IDN spoofing or a homograph attack. This is when scammers buy a URL that includes characters that appear to be English letters, but are actually from a different language set. Wikipedia uses the example of the Latin “c” or “a” being replaced by the Cyrillic “c” or “a,” resulting in a link that is visually indistinguishable from the real thing. Thus, a URL that looks like it says citibank.com may actually go to a rogue website.

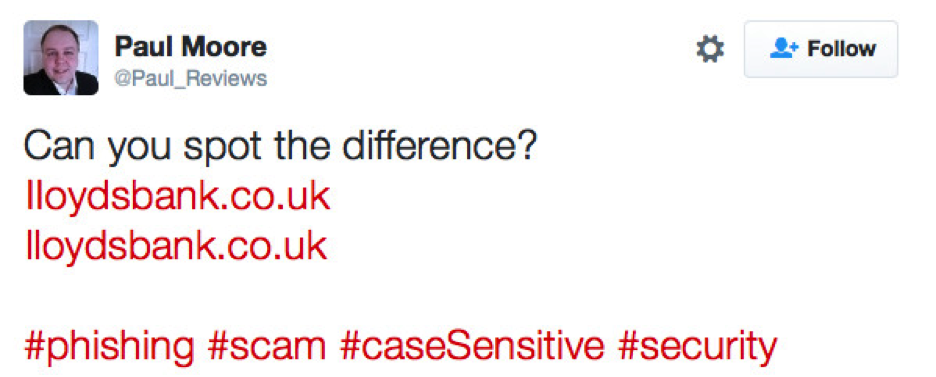

Companies like Google have fought back by restricting “suspicious combinations” of characters from appearing in Gmail messages, but this kind of spoofing can also be done by substituting one English letter for another that looks the same. A recent example was created by security consultant Paul Moore who bought www.IIoydsbank.co.uk that used two capital “i”s instead of lowercase “l”s and then challenged his Twitter followers to spot the difference. Moore went even so far as to buy a TLS security certificate, meaning it had an HTTPS connection to make the ruse even more difficult to detect.

Source: twitter.com

Mr. Moore’s example outlined the challenges for both individuals and companies to detect the difference (although it was pointed out that the company that issued the certificate could have done more due diligence). After his experiment, Moore transferred his domain to Lloyds.

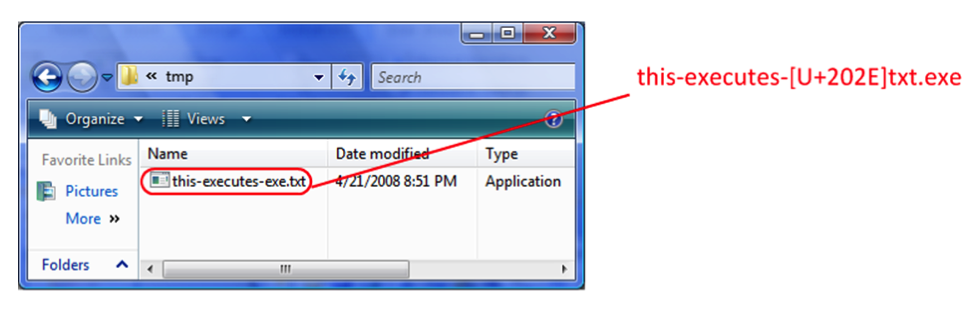

Other examples of IDN spoofing are more complex. Analyst Chris Weber went into great detail about other types of manipulations, including using invisible characters that have minimal spacing and can be surreptitiously squeezed into URLs, or “bidi,” also known as bidirectional text, that can make a file extension appear to be different from the real thing. He cites this example:

A user may think this is a simple text file, but in fact it is a dangerous executable file (he notes that Windows does recognize it as an application).

Another “bait and switch” type of attack is known as visual spoofing, where a pop-up window seems to be a secure login page to a bank and may even have a fake SSL certificate, or a Windows dialog box that asks a user for confirmation before downloading. This may claim to be a program from Microsoft or another trusted provider; but again, using some of the tricks outlined above, the real URL or file name is obscured.

Open URL redirectors

An open URL redirection is where a malicious script is tacked onto what appears to be a legitimate website address, but it takes the visitor to a phishing website without the user's knowledge. This is a less common threat, but nonetheless a vulnerability that can be exploited by hackers in unprotected websites.

A basic example could be illustrated by http://www.realwebsite.com?redirect=http://www.phishingwebsite.com

While this is pretty obviously a redirect, a longer link could be used to better hide its true destination:

http://www.realwebsite.com?%2F..%2F..%2/F..%redirect=http://phishingwebsite.com/realwebsite.php

Security researcher Dingle Yang looked into the open URL redirection vulnerabilities of a number of websites and published his findings in January 2016. He found that open source websites were particularly exploitable and cited his experiment with the learning software Moodle, where he was able to successfully create a open redirect with a few lines of code (Moodle has since patched this hole).

He also noted that login pages, which by nature redirect users, could possibly be exploited and urged web developers to always create a whitelist of accepted URLs, especially if they have more than one domain name. A discussion on a security website noted that if the site in question wasn’t vulnerable to open redirect via an outside link, the malicious code could possibly be inserted into a page if the website was hacked.

Concluding thoughts

Link manipulation is a continuing and evolving threat for both ordinary users and web administrators. While the simpler forms are easier to detect and defeat, some of the more complex methods must be prevented by writing quality code.

In short, a lot of time it’s up to the individual to discern what link is legitimate and what is a scam. Always think twice before clicking on anything, especially if it comes in the form of an unsolicited email message.

If it’s from a bank or other institution, use a bookmark or manually type in the URL – but double check you don’t make any spelling mistakes. As we’ve shown, even the smallest typo can be devastating.

Phishing simulations & training

To learn more about how to avoid phishing scams and to educate others in your company, please join Infosec IQ for free and explore more of the materials in our learning center.