Enterprise Security: A practitioner's guide - Chapter 1

Chapter 1

Security: A working definition

- Managing Risk

- Probability of Occurrence

- Business Impact

- Threat Sources

- Human Threats

- Geographic Threats

- Natural Threats

- Technical Threats

- Security as a Business Enabler

- Government Regulations

- Litigation

- Public Perception

- Corporate Espionage

- Cyber-warfare

- Security Objectives

- Summary

- References

Security is defined in various ways, depending on perspective. Business managers might see it as a collection of pesky, cost-increasing regulatory mandates. Information technology (IT) professionals might see it as competition with the bad guys; the player who wins owns the network. Security defined in these and other limited ways is not really what security professionals should support every day.

What we need is a working definition of security that shows how it adds value to an organization. For example, protecting customer privacy enhances customer retention and limits customer-driven litigation. Another example is maintaining the availability and accuracy of information necessary for business operation. Yet another is the protection of competitive advantage by safeguarding intellectual property. These examples all have one thing in common: managing risk.

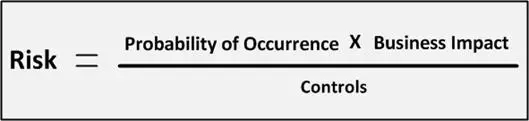

Information security is information risk management. It requires the same disciplines as other business risk mitigation activities. The main difference is in the threat/vulnerability pairs addressed. For our purposes (See Figure 1),

Security ensures the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information assets through the reasonable and appropriate application of administrative, technical, and physical controls, as required by risk management.

Figure 1: Information Security

In the following pages, we look at why risk management is necessary and the various controls used to mitigate business exposure to threats. Keep in mind that no specific control is implemented in exactly the same way in every business. The concept of "reasonable and appropriate" should always prevail.

Managing Risk

Before we can build our defenses, we have to know what we are protecting against how exposed we are. This is often a difficult concept to understand. After all, we are informed every day about vulnerabilities in applications and operating systems that might cause the collapse of civilization as we know it. However, vulnerabilities do not always unacceptably elevate an organization's risk.

The formula in Figure 2 is a common representation of how to calculate risk. The values of probability of occurrence and business impact are directly related to risk value. For example, if business impact goes up, risk goes up. The value of controls is inversely related to risk. The better the controls, the lower the risk. Our goal is to reduce risk to a level acceptable to management, not necessarily to zero.

Figure 2: Risk Formula

Probability of Occurrence

Probability of occurrence (PO) is the product of one manageable value and one nearly unmanageable value: vulnerabilities and threats. Vulnerabilities are weaknesses in a system, network, or process. A more business-focused definition would be weaknesses in people, processes, or technology. Threats are technical, human, or natural events—either accidental or intentional—that exploit vulnerabilities. The probability that a threat will exploit a vulnerability depends on the existence of the threat, the accessibility of a required vulnerability, and the effectiveness of preventive controls.

Vulnerabilities

Vulnerabilities are manageable because we control where and when they occur… or at least we try. For example, Microsoft releases patches on the first Tuesday of every month. Most of the patches eliminate vulnerabilities. If we apply the patches, we deny existing or emerging threats a means of attacking Windows. We also eliminate multiple vulnerabilities when we use locks to deny unauthorized data center access. Eliminating vulnerabilities is limited only by vendor diligence, our ability to detect weaknesses, and our organization's willingness to include vulnerability remediation in the annual budget.

Threats

Vulnerabilities do not elevate risk in the absence of related threats. However, there is almost always a threat ready to take advantage of a network, system, application, or human weakness. According to NIST (2006), a threat is

Any circumstance or event with the potential to adversely impact organizational operations (including mission, functions, image, or reputation), organizational assets, or individuals through an information system via unauthorized access, destruction, disclosure, modification of information, and/or denial of service. Also, the potential for a [threat agent] to successfully exploit a particular information system vulnerability (p. 9)

Simply, a threat is something with motive and means that, with a reasonable degree of probability, will exploit one of your vulnerabilities. The means used by a threat is known as a threat agent. A threat agent is either, "1) intent and method targeted at the exploitation of a vulnerability or 2) a situation and method that might accidentally trigger a vulnerability" (Stoneburner, Goguen, & Feringa, 2002, p. 12). For example, a worm and a keystroke logger are threat agents.

One very important objective of security is to hinder or prevent threat agent access to the target vulnerability. Advanced persistent threats, however, keep trying, and trying, and trying, and…

Advanced Persistent Threats

There is much talk about advanced persistent threats (APT), and most of it is wrong. Many victim organizations like to tag successful breaches with APT as the cause because it creaes the appearance of helplessness instead of negligence. However, an APT is a very specific type of threat.

An APT is a human or an organization conducting a campaign against a target, with malicious or criminal intent, characterized by the determination of the threat and the resources it is willing to expend to achieve the objective (GTISC & GTRI, 2011). In most cases, the attack continues until the cost exceeds the benefits of success. A Trojan inadvertently invited onto your network is not necessarily—and usually is not—an APT.

Business Impact

Business impact is the aggregate negative effect of a security incident—a vulnerability exploited by a threat agent—on an organization. Impact is usually measured as short- or long-term financial loss.

Controls

Controls help prevent, detect, or respond to threat agent attempts to exploit our vulnerabilities. They fall into three categories: administrative, technical, and physical.

Administrative Controls

Administrative controls include policies, standards and guidelines, and procedures. Security policies clearly state management intent. For example, an acceptable use policy might state that employees may not remove data from the company network. Note that the policy does not say how this will happen; it simply says that management does not want it to happen. It states a security "what", but not a "how."

Standards and guidelines enforce policy by documenting how IT and other business groups will meet policy intent. Employees must comply with standards and do their best to comply with guidelines. In our data removal example, standards might include:

These standards might be mandated by senior management or by relevant regulation. For example, the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) contains many standards dictating what the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) deems necessary to protect electronic health information (ePHI). Regardless of the source, IT and business managers must appropriately adhere to standards and reasonably comply with guidelines.

IT and business employees maintain consistent compliance with policy, standards, and guidelines by following documented procedures. In our example, a desktop build document might include a step to disable all USB ports. If the organization centrally manages end-user device ports, the step to disable USB capability might be in group policy object documentation. Including steps to achieve standards and guidelines helps ensure employees will not forget to do what is expected.

Administrative controls also include response capabilities. It is unreasonable to believe our organizations will never fall victim to a successful intrusion. So we have to prepare to mitigate business impact. This is the role of incident response teams and procedures. The purpose of incident response is to

-

Contain and eradicate the threat agent

-

Restore business processes to normal

-

Improve failed controls or implement missing controls

Finally, policies and supporting documentation have little value if employees do not understand why they exist and why they are important. We resolve this "ignorance of the law" issue with security training and awareness activities. Users are an organization's biggest control, its biggest asset, and often its most welcoming vulnerability. We must tune them like we would an intrusion prevention/detection device.

Technical Controls

Technical controls enable prevention, detection, and response using security-focused hardware and software. Examples include,

- Authentication methods

- Passwords

- Smart cards

- Biometrics

- Encryption

- Anti-malware solutions

- Intrusion prevention/detection systems

- Firewalls

- Security information and event management solutions

Physical Controls

The purpose of physical controls is to detect intruders and slow their advance long enough for law enforcement or internal security personnel to apprehend them. Physical security includes,

Layered Controls

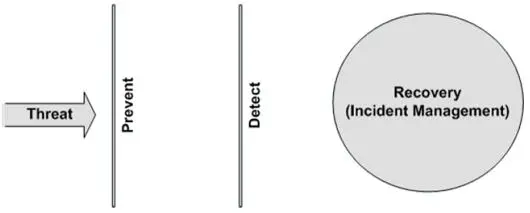

No single control or control category is sufficient to stop a determined attacker, especially APTs. Consequently, controls must support each other in layers, with one helping to detect or block what adjacent controls fail to prevent. This is called a layered defense or a defense in depth, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Defense in Depth

Controls, such as firewalls and intrusion prevention systems, first attempt to prevent a threat agent from entering the network or reaching its target. If the threat agent cracks this first line of defense, other controls detect anomalous network or system behavior. Detection controls include proactive log management and intrusion detection systems. Once detected, response teams react to contain and eradicate the threat agent and restore business processes to normal.

Threat Sources

Understanding the probable threats facing your organization's network requires an understanding of where threat agents originate. Not all threat sources apply to your business. For example, if you assess a facility in Toledo, Ohio, you don't have to worry about hurricanes. However, you might want a business continuity plan that includes blizzards. For our purposes, threat sources fall into one of four categories: human, geographic, natural, and technical.

Human Threats

Human threat sources include both internal and external people. Further, human-caused security incidents are either accidental or intentional. Regardless of location, a human threat source relies on three common conditions for successful vulnerability exploitation: motive, opportunity, and means (MOM). Understanding how they work and what to look for helps us design reasonable and cost effective prevention and detection controls.

Motive

Motive is a person's reason for doing something. It is often defined in terms of incentive, what a person hopes to gain. Successful defense against a threat agent depends largely on the person's incentive for reaching targeted information assets. For example, if an attacker can sell the contents of a target database for $500,000, he or she is probably much more motivated than the attacker stretching for assets worth a few hundred dollars. Another example is the politically motivated terrorist who believes a successful attack will advance his movement's agenda. Motive can mean the difference between facing a traditional threat and an APT.

How we determine the probable motive behind an attack depends on several factors. We can often identify high-risk factors by asking the right questions, including:

- Is your organization participating in politically sensitive business operations?

- Do you process or store information of high-value to cyber-criminals or foreign governments?

- Are your hiring, termination, and labor practices fair and impartial as perceived by the public?

- Are you a high-profile organization that makes a great publicity target (e.g. Google, Yahoo, Microsoft, etc.)?

This is a short list that provides examples of the types of questions you might consider. They often change based on the system or the facility assessed. For example, you might determine there is potential for high motivation when assessing engineering systems on which you create and store intellectual property. On the other hand, systems containing personal employee information, while worthy of protection, probably face less motivated threat agents.

Opportunity

Understanding opportunity is easy; how many unmanaged vulnerabilities do you have? Opportunity increases with

- The number of patches you do not apply

- The level of security training and awareness activities in which your employees participate

- The effectiveness of prevention controls

- The effectiveness of detection controls

- The speed at which your incident response team (assuming you have one) contains threat agents

Means

Means is determined by the skill set required to reach and exploit a target. An attacker has the means if he or she can circumvent your controls and successfully achieve planned objectives. When designing a controls framework, it is not always necessary to fill your network with performance-killing and hard-to-manage security appliances. Rather, simply increasing the skill set and tools required by the attacker reduces probability of occurrence.

Human threat agents, therefore, are hindered by decreasing their motives, eliminating or confounding their opportunities, and requiring them to have sophisticated toolsets and skills.

Human Threat Agents

Human threats use a variety of methods, including social engineering, phishing or pharming, DNS redirection, and botnet operation. An attack against an organization, especially an APT, will use two or more of these or other methods. This is called a blended threat.

Social Engineering

Social engineering uses con artist skills to achieve an objective. For example, an attacker might call a user in payroll. The conversation begins with the attacker telling the payroll user that he is with the help desk and trying to remotely install new software. However, he needs the user's password to complete the task. Untrained employees, or those working in an organization without strong awareness activities, are probable vulnerabilities for social engineering. In addition to logical access information gathering, social engineering is also a great tool for gaining unauthorized physical access.

Phishing and Pharming

Phishing and pharming are types of social engineering, typically using email or DNS redirection. An attacker might craft an email to look like it comes from a popular social networking site. She then sends it to a large set of email addresses. Organizations not filtering questionable email will likely allow their users to receive it. An untrained user will open the email and click on a link provided by the attacker.

Clicking on a link in a phishing email might perform one or more of the following:

- Install botnet software on the user's computer

- Install key logging software

- Redirect the user to a website masquerading as a page belonging to the social network

- Request the user's account information, including password

- Request the user's payment information, including credit card approval information

DNS Redirection

One of the possible results of phishing is website redirection. In phishing, this might simply be a one-time event. However, redirection is also caused by DNS (Domain Name System) cache poisoning. The user will go to a malicious site every time his computer requests an address from a compromised DNS server or from his computer's compromised local DNS cache.

Botnets

Botnets manage much of today's phishing, DNS redirection, information gathering, and other attack-related activities. Human controllers build a network of end-user systems and servers by using social engineering or some other method to install an agent on as many computers as possible. The agents can perform any task, including

- Gathering sensitive information during day-to-day activities

- Launching denial of service (DoS) attacks against the host or other organizations

- Launching phishing attacks

Botnets are an excellent resource for APTs. The attackers simply request information about the target organization from botnet operators. Information from individual systems might include

- Operating system used

- Applications installed

- Patch and version levels

- Network information

- Anti-malware solutions

There are other human threat sources, but these are the most common causes of system and network compromise.

Geographic Threats

Specific conditions in the region or country in which a facility is located might have a unique set of geographic threats, including

- Political instability

- Social unrest

- Economic instability

- Frequent power issues

- Frequent communication issues

- Uncertain or antagonistic legal environment

Natural Threats

Natural threats are thrown at us by nature. Varying by location, they include

- Tornados

- Earthquakes

- Hurricanes

- Wild fires

- Severe thunder storms

- Floods

Technical Threats

I use this category for all electronic threats not directly managed by a human. For example, there are an uncountable number of malware instances floating around the Internet. They range from simple viruses to sophisticated worms. They infect servers, desktops, laptops, and smartphones. Usually caused by user action, infestations by these unmanaged applications can cause internal denial of service, system failure, or simple customer frustration.

The threats listed here are not intended to be inclusive of everything you might face. In fact, attackers are far too creative to list everything they might try to do to our networks. However, this sampling provides a view into the types of agents that contribute to organizational risk and our job security.

Security as a Business Enabler

Security should enable a business to operate as needed, without fear of malicious interruption, litigation, or public relations damage. Often, this is difficult given the security-related challenges to business success, including

- Government regulations

- A litigious operating environment

- Public perception

- Corporate espionage

- Cyber-warfare

Government Regulations

In the United States, an organization might face local, state, and federal regulations telling them how to protect certain types of information. Also included are clear sanctions for non-compliance. Multi-national companies also encounter similar, and often more stringent, regulations abroad.

Understanding local and state regulations is outside the scope of this article. Consequently, I focus on key federal regulations and how they affect relevant industries.

GLBA

The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA), also know as the Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999, requires covered entities to protect consumer privacy. Organizations affected include any entity involved in banking, insuring, stocks and bonds, financial advice, and investments.

The GLBA, with a focus on confidentiality, requires covered entities to:

HIPAA

The objective of the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 is protection of the confidentiality, accuracy, and availability of personal health information (PHI). The HIPAA consists of a privacy rule and a security rule. As security professionals, correct implementation of the security rule's standards and guidelines is crucial in our business enablement role.

Entities covered by the HIPAA include:

- Any provider of medical or other health care services or supplies

- Health plans

- Insurance

- Medicare

- Medicaid

- Health care clearinghouses that process another covered entity's billing or other transactions

- Medicare prescription drug card sponsors

Unlike other regulations, the HIPAA includes specific standards and guidelines for implementing security. Standards are "must do's" and guidelines are recommendations. When assessing an organization's compliance with HIPAA standards, a security professional can recommend and document one of the following:

- Implement the standard, if reasonable and appropriate given unique business conditions (e.g. available budget, compensating controls, operational issues, etc.). If management determines a standard is not reasonable, it must

- Document its reasoning, or

- Implement one or more compensating controls

- Do nothing if any of the steps defined in number 1 are deemed unreasonable and inappropriate for the business.

Security should assist management with documenting any deviation from standards. Keep the documentation handy if you need to justify why expected controls are missing from your security controls framework.

FISMA

The Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA) is Title III of the E-government Act (public law 107-347) passed in 2002. Its purpose is to ensure that agencies of the United States government take appropriate steps to protect sensitive information, including:

- Periodic risk assessments

- Policies that reduce risk to an acceptable level

- Subordinate plans for providing "adequate" information security for networks, facilities, systems, etc.

- Security awareness training

- Periodic gap analysis

- Remedial action plans

- Detection and response procedures

- Business continuity plans

Essentially, the FISMA requires federal agencies to implement basic security controls and processes.

SOX

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX) is intended to ensure the accuracy and transparency of financial reporting in publicly traded companies. However, security managers and auditors are affected by a small part of the act: Section 404. It reads

(a) RULES REQUIRED.—The Commission shall prescribe rules

requiring each annual report required by section 13(a) or 15(d)

of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (15 U.S.C. 78m or 78o(d))

to contain an internal control report, which shall—

(1) state the responsibility of management for establishing and maintaining an adequate internal control structure and procedures for financial reporting; and

(2) contain an assessment, as of the end of the most recent fiscal year of the issuer, of the effectiveness of the internal control structure and procedures of the issuer for financial reporting.

(b) INTERNAL CONTROL EVALUATION AND REPORTING.—With respect to the internal control assessment required by subsection (a), each registered public accounting firm that prepares or issues the audit report for the issuer shall attest to, and report on, the assessment made by the management of the issuer. An attestation made under this subsection shall be made in accordance with standards for attestation engagements issued or adopted by the Board. Any such attestation shall not be the subject of a separate engagement.

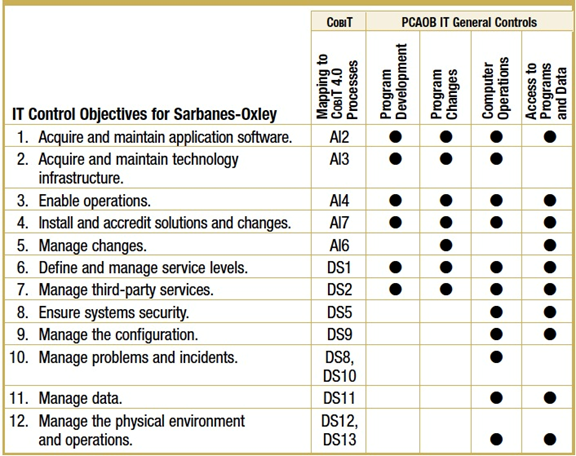

While they might seem innocuous, an entire accounting practice has grown up around these 173 words. The Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) uses SOX guidance from the Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) to determine how to audit covered entities. Auditors typically use the COBIT framework to identify key controls and measures of compliance. Figure D shows how PCAOB guidance maps to COBIT.

Figure D: Mapping COBIT v. 4 to Sarbanes-Oxley Requirements (IT Governance Institute, 2006, p. 11)

Litigation

In addition to regulatory compliance issues, executives might find themselves standing in front of a judge because of perceived negligence. Many consumers become quite angry when proper steps are not taken to protect their privacy. Writing checks for lawyers and plaintiffs is not what the investors intended for their money.

It is our job to help management understand the consequences of improperly managing information security; if they do not allocate budget now, they certainly will later. They will become part of a group of managers from organizations that manage security to protect a bottom line that is shrinking because of perceived negligence (Ahmadi, 2011). It is better to plan ahead that to react.

Public Perception

Public perception is also a factor in bottom-line behavior. Unhappy customers do not have to hire an attorney to cause damage; they can just go somewhere else to purchase products and services. In a world of Internet commerce, it is not hard to find an organization that acceptably protects privacy and due diligence.

Corporate Espionage

Maintaining a competitive edge is difficult. In many industries, gaining and keeping market share requires continuous product innovation. Letting your competition in on what you are planning allows them to release the same or similar product at the same time, cutting your leading edge profits. In some cases, recipients of your organization's intellectual property might actually beat you to market, relegating your company's release to "wannabe" status…

Data owners of intellectual property should assign it the same data classification as protected customer and employee information: or higher. Without regulations mandating protection of company assets, it is important you ensure management understands the importance of preventing leaks.

Cyber-warfare

Until a few years ago, most people had never thought of warfare across the electronic frontier. However, things have changed. The United States, Russia, China, Israel, and North Korea are all apparently building cyber-warfare capabilities (Marzigliano, 2011). In addition, we face aligned and non-aligned terrorist organizations and vigilantes (e.g. Anonymous). Any critical infrastructure is vulnerable, including utilities, financial institutions, and community services.

It is an incorrect assumption that an organization must be a government agency or contractor to make the list of possible targets. Any organization can fall prey to these APTs.

Security Objectives

I close this article with a look at information security objectives. Every control—administrative, physical, technical, preventive, detection, and response—should focus on achieving reasonable and appropriate

Summary

As business enablers, it is our jog as security professionals to protect the confidentiality, accuracy, and availability of our organizations' information assets while ensuring productive business operation. We do this by applying reasonable appropriate controls resulting from periodic risk assessments.

We cannot protect against what we do not understand. Human threat success grows with our ignorance. Sun Tzu wrote in The Art of War:

All warfare is based on deception. Hence, when able to attack, we must seem unable; when using our forces, we must seem inactive; when we are near, we must make the enemy believe we are far away; when far away, we must make him believe we are near. Hold out baits to entice the enemy. Feign disorder, and crush him.

It is our responsibility to block deception wherever we can by understanding why attacks happen, how they happen today, and how they might happen tomorrow.

In addition to threats, we must also consider local, state, and federal regulations. It makes no sense to protect the bottom-line from intruders and then write sanction checks to government agencies.

The objectives of security are few, but often difficult to achieve. With perseverance, diligence, and a thorough understanding of what our organizations' face every minute of every day, however, basic security goals are reachable and maintainable.

References

Ahmadi, M. (2011, January). The Security Professional and the Legal Environment. ISSA Journal , pp. 25-27.

Cisco Systems. (2011). Cisco 2Q11 Global Threat Report.

GTISC & GTRI. (2011). Emerging Cyber Threats Report 2012. Retrieved November 23, 2011, from Georgia Tech: www.gtisc.gatech.edu/doc/emerging_cyber_threats_report2012.pdf

IT Governance Institute. (2006, September). IT Control Objectives for Sarbanes-Oxley. Retrieved December 1, 2011, from ISACA: http://mcaf.ee/i7l30

Marzigliano, L. (2011, October 27). The Pandora's Box of Cyber Warfare. Retrieved December 2, 2011, from InfoSec institute: /cyber-warfare/

NIST. (2006, March). FIPS Pub 200, Minimum Security Requirements for Federal Information and Information Systems. Retrieved November 23, 2011, from National Institute of Standards and Technology: http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/fips/fips200/FIPS-200-final-march.pdf

Stoneburner, G., Goguen, A., & Feringa, A. (2002, July). Risk Management Guide for Information Technology Systems, NIST Special Publication 800-30. Retrieved November 9, 2011, from National Institute of Standards and Technology: http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-30/sp800-30.pdf