Privacy Implications of Automatic License Plate Recognition Technology

ALPR – Technical Specifications

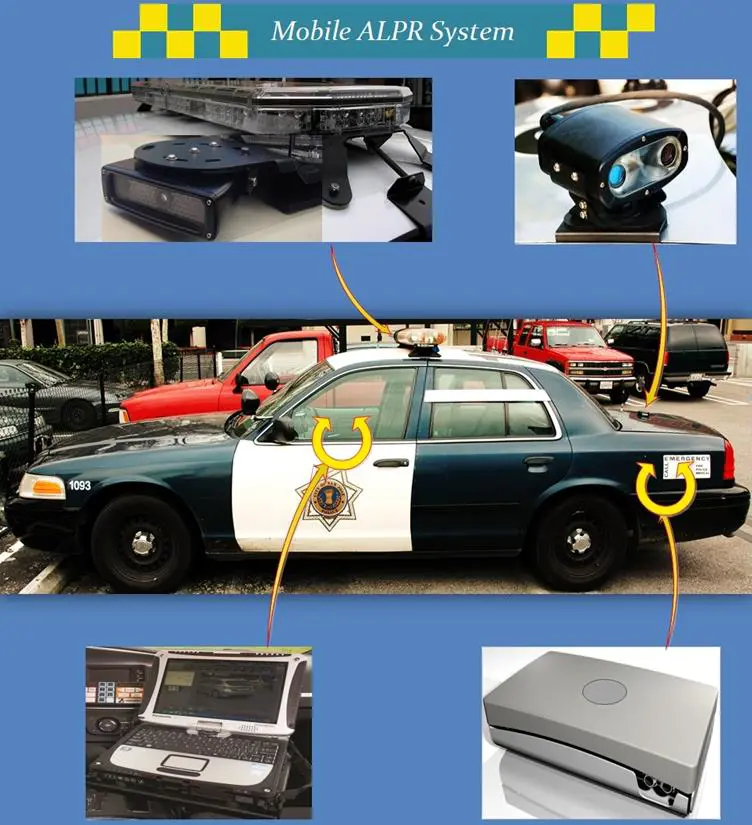

The majority of ALPR devices are mounted on bridges, road signs, and poles near traffic lights or outside public buildings and even patrol vehicles. It seems that the last type of carrier, presumably for its mobility, arouses the most interest and concern among people. Mobile ALPR systems consist of (See Diagram 1):

Camera

Presently, most of the ALPR systems utilize a dual-channel set – one high-resolution digital and one infrared illuminated camera. The latter appliance is used to suppress ambient light, soften plate reflectivity, and take pictures at any time of the day.

Mobile ALPR cameras can be integrated either into the light bar or mounted on the roof or trunk of patrol cars. Images of vehicles passing in both directions are captured and processed constantly. According to one vendor, its cameras are capable of photographing up to 60 plates per second at speed of more than 65 miles per hour.

Diagram1

a) ALPR Cameras /above the police car/

b) Processor /bottom right corner/

c) User Interface /bottom left corner/

Mobile ALPR Processor & Software

Normally, in-car mobile processors are capable of servicing up to four dual-channel ALPR devices. As a matter of efficiency, the process should be powerful enough to accommodate speeds of more than 100 mph.

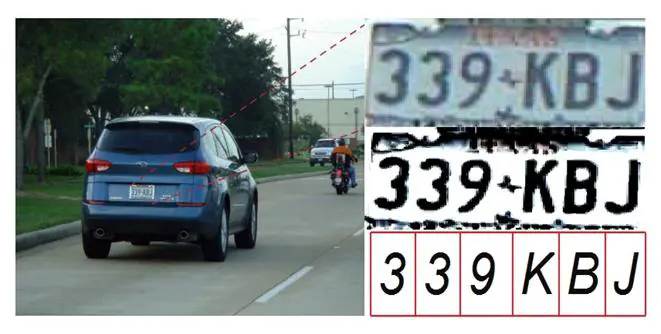

Additionally, joint computational capabilities between processor and application procure optical charter recognition (OCR), which is a sophisticated process that transforms an image of a plate into alphanumeric characters.

In order to complete the entire identification procedure from start to finish, the software applies six primary algorithms:

1. Plate localization

2. Plate orientation and sizing

3. Normalization

4. Character segmentation

5. Optical character recognition (OCR)

6. Syntactical/Geometrical analysis

Diagram 2

"ALPR Algorithms at Work"

Once this procedure is completed, the plate number is then stored, time-stampled, and tagged with a given location. The new plate log is then run against pre-existing database, or "hotlist," and if there is a match ("hit"), the police officer is instantly alerted.

User Interface

In the case of vehicle-based ALPR systems, captured images are displayed on a user interface, which is a dedicated computer specially designed for ALPR system or in-field notebook rigged out as such.

Circumvention Techniques

There are a number of methods that can be used in order to avoid detection: plate cover and spray are good suggestions, but one is always at the risk of being imposed a fine. On the other hand, car cloning, which is when one copies registration plates from another similar vehicle, is a technique that has been in upsurge for quite a while. Even an increase of reflective letterings in order to obstruct ALPRs is proposed in theory by one auto expert.

Benefits of ALPR

Police communities usually use license plate readers to enforce parking restrictions or identify offenders who run red lights. Nevertheless, police departments, in bigger cities especially, use this novice technology to scan parking lots, catch thieves, and identify motorists with open warrants.

LPR technology is considered directly responsible for recovering over 3,600 stolen vehicles and has led to issuing summons to almost 35,000 unregistered cars, according to NYPD.

Virginia police county reports that owing to license plate info, they managed to recover 529 stolen cars, 751 stolen license plates and arrest 229 wanted persons.

Homicides are not left out of the equation as well, with five people arrested in Long Beach, CA, after scanner data placed them at the murder scene. In Europe, yearslong shooting sprees in Germany were successfully attributed to a serial drive-by-shooter again because of the ALPRs. The cost of him being nabbed, however, comes in the form of 60-80 million images, with metadata attached, taken from innocent people.

On top of everything mentioned so far, LPR systems may contribute to reduced distractions and road accidents among police staff, since officers are not obliged to pay attention to passing automobiles (i.e., the device will give a warning if there is a "hit).

As these results show, the ALPR system "works 100 times better than driving around looking for license plates with our eyes." Furthermore, the LAPD Chief firmly believes that this technology has "unlimited potential" as an investigative tool. One could extract the real value, however, only for the long haul, by amassing immense amounts of data that would allow creating patterns of movement based on specifically a defined location.

Enormous ALPR Databases

A new ALPR database in California is being prepared, apparently to accommodate the ever increasing number of license plate reads. Just for the record, its precursor managed to preserve more than 160 million data points logged by LAPD.The local agencies in San Diego itself have compiled more than 36 million license plates entries in a regional digital storage since 2010.

The reads build-up in Maryland's state data fusion center reached the staggering number of 85 million in 2012 alone. What strikes privacy activists as concerning, however, is that on an average "only 0.2 percent of those license plates, or about 1 in 500, were hits" and that "for every one million plates read in Maryland, only 47 were potentially associated with more serious crimes."

Diagram3

"Plates Read-Hits-Serious Crimes" Imbalance

LPR Data is not Considered Personally Identifying Information

As far back as 2006, the deputy commissioner and counsel at the NY State Division of Criminal Justice Services Gina L. Bianchi wrote that there "does not appear to be any legal impediment to the use of a license plate reader by law enforcement." In fact, an LPR is nothing else than an equivalent of the outdated manual entering of license plate information.

LPR data does not directly identify a specific human being, thus such information is not considered personally identifying. This contention is also underpinned by the Driver's Privacy Protection Act, 18 U.S.C.A. §§ 2721-25. Yet, in a 2009 report issued by the International Association of Chiefs of Police is stated that "once that fact-based LPR data is analysed, it may become intelligence data in the future and be subject to the U.S. Department of Justice's regulations contained at 28 C.F.R. Part 24."

Tracking Patterns

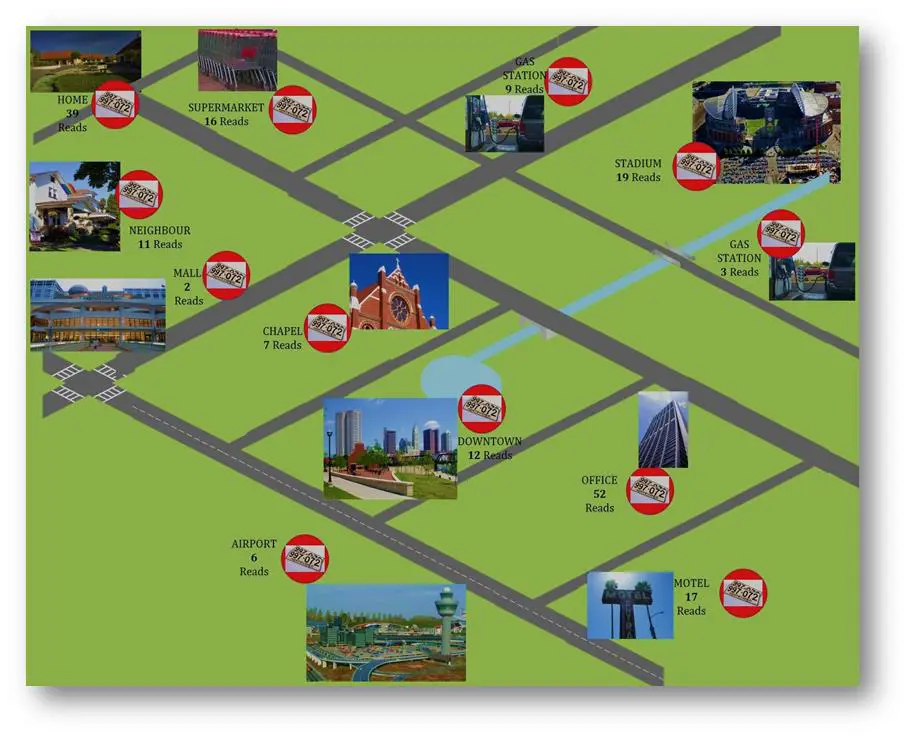

Owing to the software provided by Palantir to law enforcement services, analyzing vast quantities of crude data, which seemingly have no common ground, is not impossible anymore. The system functions by piecing together all data points, i.e., scraps of information concerning one or series of objects in close proximity — location data and geo-searches, notes and photos, calls for service, relevant arrest data, anonymous tips, social engineering, etc.—visualized oftentimes in the form of charts, graphs, and real-time statistics.

Developed on the PayPal concept of preventing cyber fraud, this multipurpose software can 'foresee' or track down anything from foreclosures to notorious terrorists. Yet to work effectively, considerable amount of data is needed. The more the data available, the better the final result, actually.

Quick access to a user-friendly interface at hand in combination with unique analytical properties makes this tool the supreme IT forensic software, an invaluable aid to any investigator.

Transferring all said to the ALPR system scenario,

a single license plate image being captured is not problematic. Nevertheless, a compounded mixture of information extracted from numerous reads collected consistently over time may expose a very revealing picture of the movement pattern associated with the person behind the wheel (See Diagram 5). Then in the course of time, many vehicles in a given covered area will not escape notice.

Access & Retention Policy

Most reports on access to private databases by law enforcement staff are rather contradictory. While one source confirms that most officers have provisional access, others ascertain to the contrary—"only a handful of police personnel had access to it."

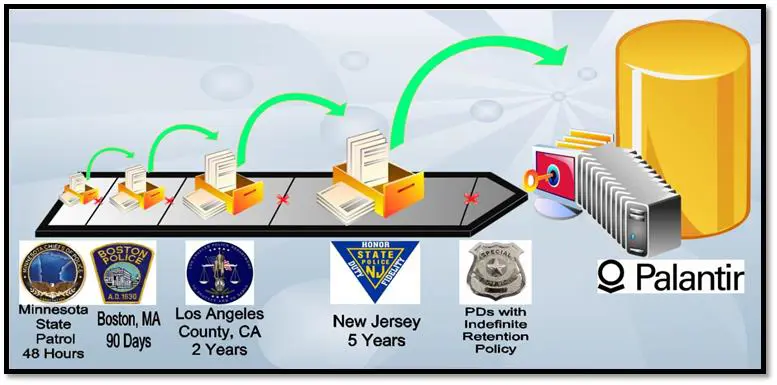

Retention generally refers to the license plate data that has not been flagged as part of an incident or investigation. Several states including Maine, Virginia and New Hampshire (where the use of ALPRs is banned) have tight time-frame limitation on keeping the newly reaped data and they dispose of it within hours, days, or just a couple of weeks. On the other hand, many police authorities in other states have few or no regulations over the utilization of masses of incoming information. Los Angeles County (2 years) and New Jersey (5 years) can be cited as examples of those that have long retention policies; Milpitas, CA, along with Yonkers, NY, are such that keep the database for an infinite time.

And even if in one place the retention period is short, it gives no guarantee that the information will not proliferate one way or another, especially given the fact that law enforcement agencies share ALPR data on a case-by-case basis. British agencies, for instance, routinely exchange information with one another and thus many organizations benefit from the software created by Palantir to store and analyse license plate data without having used it themselves.

Speaking of Palantir, the Silicon Valley-based organization can also acquire every piece of data residing in servers of law enforcement agencies that are their clients, and keep it in their repository indefinitely, presumably for research purposes. In exemplification of how LPRS data can leap over databases of states that have different retention policies timewise, and just wind up hanging there ad infinitum, you can see the graph below.

Diagram 4

"Retention of ALPR Data after Local Retention Limitation is over"

Update: The Boston Police Department has suspended the use of ALPRs (Read more)

Potential Misuses of LPR Data

Extortion

In 1998, Washington, D.C. police officers pleaded guilty to extortion for standing outside gay bars, collecting information on visitors with whom later on they made contact and blackmailed.

Institutional abuse

An anti-war demonstrant from the UK was pulled over when a license plate reader registered a "hit". The license plate was hotlisted as a result of the victim's participation in an anti-war protest.

On Sale

According to one article, the California firm Plate Scan, out of business in 2012, was retaining at that time "about four years' worth of license plate data." All those stored logs were ready to be sold to whomever is willing to pay the price.

Chilling Effect

The term "chilling effect" is associable with the people's psychological restraint on exercising their protected rights of protest, expression, political participation and association since they fear or expect to be under constant surveillance. In the wake of the NSA scandal, such a phenomenon was noticed in the behavior of many U.S. citizens.

Privacy Concerns

ALPRs have come under slashing criticism from privacy groups like ACLU and EFF, which brought to trial the LAPD and County Sheriff's Department in May 2013 for refusing access to a week's worth of license plate records.

Privacy concerns regarding tracking movement of ordinary citizens have not one or two arguments. On the legal side, a February legal opinion made by Virginia Attorney General Ken Cuccinelli on the aggregation and dissemination license plate reads outlines "collecting and storing such data in a "passive manner" that is not directly related to a criminal investigation as an action that would most probably be in violation of the state's Government Data Collection and Dissemination Practices Act."

Even the International Association of Chiefs of Police established in a report that "recording driving habits" may violate First Amendment since recording devices could snap your vehicle next to places, events, buildings and persons; photographs do not capture the license plate only, they may contain the vehicle, occupants and immediate vicinity (See Diagram 5). A bright example of that is the first-hand account of an L.A. community activist and blogger who after receiving more than ALPR100 photos from local officials discovered with fright that in one of the photos his entire family had been snapped.

The frequent nonexistence of firm policy or regulations over use of ALPRs other than they should not be utilized to locate individuals of personal interest (spouses, friends, foes) is also alarming.

Diagram 5

"A Year in the Life of an Ordinary Person through the Eyes of ALPR Technology"

/Fictional Illustration/

With relation to the retention of ALPR records, privacy advocates demand shorter time frames, extendible only by warrant in the event of exigent circumstances, and further access granted by court.

ACLU believes that security should not always have priority over civil liberties, especially in a situation when privacy of innocent people clearly outweighs minimal potential benefit to law enforcement (See again Diagram 3). Maintaining huge databases on personal movements of law-abiding people in perpetuity just doesn't seem right to them. At a minimum, it may psychologically affect people, as already noted.

And one more time, "yes," affirmative, your license plate data gives away your identity and movement pattern, just like the attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation once said: "This is like having your barcode tracked." "Future use" pretext simply doesn't provide enough justification to treat everyone as a potential criminal. One way or another, it reintroduces generally the same debate as the NSA mass surveillance — What would you prefer if you can't have both simultaneously: safety or privacy?

At the end of the road still hangs one more question: "Who is collecting the information…is it just the police?" — The ALPR technology indeed is not confined to government agencies. Moreover, the man-on-the street's logic is plain; you need just to look at the other clients of Palantir (CIA, FBI, DOD, USIC, Marine Corps, etc.; Note: Palantir denies any business relationship with NSA), the company that has the almighty magic orbs /referring to the Tolkien's "Lord of the Rings" and the name of the firm/ that assume the form of computer program in our world. Under the circumstances that NYPD and LAPD use the same software, it will not be easy for you to convince anyone else that all these mighty institutions, which strike the ordinary person with awe, do not have at least a pinch of the richness that ALPR data represent.

Reference List

3M. 3M Mobile ALPR Camera Systems. Retrieved on 20/12/2013 from http://solutions.3m.com/wps/portal/3M/en_US/NA_Motor_Vehicle_Services_Systems/Motor_Vehicle_Industry_Solutions/product_catalog/3m-automatic-license-plate-recognition/mobile-alpr-camera-systems/

ACLU (2013). You are being tracked. Retrieved on 20/12/2013 from https://www.aclu.org/alpr

Badger, E. How Much Do Automated License Plate Readers Know About You? Retrieved on 20/12/2013 from http://www.theatlanticcities.com/technology/2013/05/how-much-do-automated-license-plate-readers-know-about-you/5525/

Farivar, C (2012). Your car, tracked: the rapid rise of license plate readers. Retrieved on 20/12/2013 from http://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2012/09/your-car-tracked-the-rapid-rise-of-license-plate-readers/

< span>International Association of Chiefs of Police, (2009). Privacy impact assessment report for

the utilization of license plate readers. Retrieved on 20/12/2013 from http://www.theiacp.org/Portals/0/pdfs/LPR_Privacy_Impact_Assessment.pdf

Kravets, D. (2013). License Plate Readers Track You for Profit. Retrieved on 20/12/2013 from http://www.wired.com/threatlevel/2013/07/license-plate-readers/

Martinez, M. (2013). Policing advocates defend use of high-tech license plate readers. Retrieved on 20/12/2013 from http://edition.cnn.com/2013/07/18/us/license-plate-readers/

Paganini, P. (2013). NSA Surveillance Is Changing Users' Internet Experience.

Roberts, D. & Casanova, M. (2012). Automated License Plate Recognition Systems - Policy and Operational Guidance for Law Enforcement. Retrieved on 20/12/2013 from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/239604.pdf

Schreiber, R. (2013). Would License Plate Reader Jammers Work And Be Legal? Retrieved on 20/12/2013 from http://www.thetruthaboutcars.com/2013/06/would-license-plate-reader-jammers-work-and-be-legal/

Wikipedia. Automatic number plate recognition. Retrieved on 20/12/2013 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Automatic_number_plate_recognition

www.platerecognition.info. Automated License Plate Recognition (ALPR). Retrieved on 20/12/2013 from http://www.platerecognition.info/1103.htm

Diagrams

Diagram 1 – Based on image provided by Ecbub. Retrieved on 20/12/2013 from http://www.ecbub.com/byp_4753124_In-Car-ANPR-ALPR.htm

Diagram 2 – Based on image in the "Algorithms" section of "Automatic number plate recognition" by Wikipedia. Retrieved on 20/12/2013 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Automatic_number_plate_recognition

What should you learn next?

Diagram 3 – Based on graph provided by ACLU on page 14 of "You are being tracked" report. Retrieved on 20/12/2013 from https://www.aclu.org/alpr