Hacktivism: Means and motivations … what else?

The term "hacktivism," derived by combining hack and activism, refers to the use of computers and any other IT system and network to debate and sustain a political issue, promote free speech, and support human rights. Hacktivism is mainly interpreted by society as the transposition of the protest and the civil disobedience into cyberspace. Hacktivism is the use of technology to express dissent, but it also represents a dangerous threat that has already crated extensive damage to the IT community with cyber attacks. On the security perspective there are two schools of thought: One considers hacktivists cybercriminals to be prosecuted, the other, despite being conscious of the menace they represent, maintains that they are anyway a voice to listen to.

This post will analyze the origin of the phenomenon, its evolution and incidence in the current social texture, and hacktivism's concrete impacts on society, internet users' habits, business security, and governments' policies.

FREE role-guided training plans

The origin

The term was coined in 1996 by Omega, a member of the popular group of hackers known as Cult of the Dead Cow. Through the years the word "hacktivism" has been used in profoundly different contexts; it has been adopted to describe cybercrimes or the misuse of technology hacking with the specific intent of causing social changes or simply to identify sabotage for political means. Politically motivated cyber attacks were recorded as early as 1989. The main motivations for the hacks were nuclear disarmament, government responses to local political disorders, and court decisions. During recent years, groups of hacktivists such as Anonymous have reached an enormous popularity all over the world and they have been involved some of most clamorous attacks against institutions, organizations, and governments.

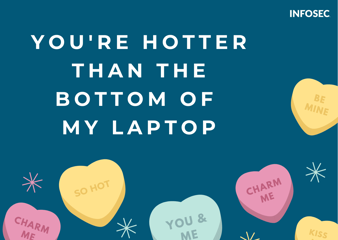

Figure 1. 2012 Cyber Attacks Statistics

Analyzing the 2012 Cyber Attacks Statistics, it easy to recognize hacktivism as one of the primary motivations behind the discovered attacks and the trend has not changed since the first part of 2013, in which the number of offensives attributed to hacktivists increased.

Groups like Anonymous are exploiting the power of modern technology for social protest and to promote political ideology. The behavior was observed for the first time in 1996 by a member of the famous group of hackers, the Cult of the Dead Cow, named Omega.

Trying to frame a wide range of currents of thought with a single term is a limiting approach; in fact, each group is characterized by different ways of hacking, different motivations, and different means used.

Groups of hacktivists are responsible for denial-of-service attacks, information theft, data breaches, web site defacement, typosquatting, and many other acts of digital sabotage. They act in the conviction that through the use of the technical tools it is possible to produce similar results to those produced by regular activism or civil disobedience to promote political ideology.

The availability of the Internet and the numerous social media have enhanced the diffusion the voice of hacktivism on a large scale. From recruiting to organizing the attacks, all is arranged online and the number of followers is virtually unlimited. A hacktivist is hidden in every one: Everyone has his or her personal perception of reality and everyone could feel the need to join in this new form of dissent. Another factor that has increased the consolidation of hacktivist movements is the deep economic crisis that has characterized the last decade.

The discontent with a global policy subservient to the interests of a few classes has fueled the growth of small groups of "web dissidents," which has given rise to movements that have changed history. Hacktivism must be examined also in the social context in which is growth, because it is an ideology and the ideology cannot be suppressed with arrest or persecution.

Analyzing the groups of hacktivist from the security point of view, it is inconceivable that their action represents a danger for the collectivity exactly as any other cybercrime.

The attacks conducted by groups of hacktivists always seem to be more structured. They have gone from defacing of non-upgraded sites to complex hacks. The offensives have produced the same effects as those perpetrated by cyber criminals or by state-sponsored hackers and the IT security community is aware that any form of cyber protest must be taken into serious consideration.

Be aware that in the past we read about security experts that equated group of hacktivists to cyber terrorists. In my opinion, this is not exact, because they never hack with the intent to hit civil people or to cause serious damage to the collectivity. Hacktivists have never hit critical infrastructures; their "modus operandi" is totally different from others and any reckless classification is harmful and misleading for those who really wish to understand the phenomenon.

The year 2010 is considered by researchers the year of consecration for hacktivism because groups of hacktivists linked to the Anonymous collective conducted an impressive number of attacks with growing frequency during the entire year.

The type of attack most diffused was the distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack; millions of followers of the hacktivists movement joined the offensive using free available tools. With this tactic, the hacktivists attempt to make a website or a web service unavailable to its users due an enormous quantity of requests sent in a short period.

But DDoS tools weren't the only weapon in the arsenal of hacktivists: Malware and phishing campaigns were conducted to gather precious information on the targets. The objectives were multiple, the disclosure of sensitive information as in the Stratfor case and the information gathering on targets of the attack. In many cases, hacktivists used hacking techniques to perform their operations involving critical masses made by ordinary people.

In the past, Anonymous supporters have used a popular program named LOIC, easily found on the Internet, that allows users to flood victims with unwanted traffic. To increase the volume of the attacks the group of hacktivists released instructions and videos on how to participate in a DDoS attack on the web.

Anonymous also improved that DDoS attack methods by deploying on the network website for massive recruiting. Users simply visiting a web page of those sites and, without any other interaction, have started to flood a target. The collective made it possible by simply hiding in the "malicious" web pages a JavaScript interpreted by the user's browser; the unique defense against it is to disable JavaScript in the browser.

The method was considered for two reasons:

- Increase of volume of the attacks.

- From a legal standpoint it is hardly attributable to each user a criminal liability. A user who participated in the attack, unlike what happened before with tools like Loic, could deny any responsibility by maintaining unaware lack of awareness of participation in the offensive. This subtle aspect could be the stimulus for a wide category of undecided who share the subject of the protest but that since that moment was scared by the possibility of committing an illegal act by participating in operations.

Anonymous

Undoubtedly the Anonymous collective is considered the incarnation of the hacktivism philosophy. The group and its operations are at the center of a heated debate. Public opinion and industry experts are divided between those who believe the collective is a group of cyber criminals to suppress and those who take due account of the phenomenon while trying to understand the real motivations behind its campaigns.

Anonymous first announced themselves to the world in 2008 with a video published on YouTube in which the collective declared war on the church of Scientology. Anonymous successfully moved the protest from cyberspace to the street, over 10,000 people assembled in major cities across the globe wearing Guy Fawkes masks manifested against the religious group. It was just the beginning.

Figure 2. Video Debut of Anonymous

In 2010 numerous Indians hired the Aiplex Software firm to launch massive DDoS attacks against websites that did not respond to software takedown notices against piracy. Hacktivists protested, promoting Operation Payback in September 2010. The original target was Aiplex Software but, upon finding some hours before the planned DDoS that other attackers had already taken down the company's website, the hacktivists launched the attacks against numerous organizations for protection of copyright and law firms.

But one of the most popular offensives of the collective occurred On April 2, 2011, when Anonymous attached Sony in a campaign named #opsony, part of Operation Payback. The hacktivists took down the PlayStation Network and PlayStation Websites. The PlayStation Network subsequently was down for a long period.

In December 2010, the website WikiLeaks was accused by US authorities for the publication of secret United States diplomatic cables. Anonymous, supporting WikiLeaks, focused its Operation Avenge Assange against Amazon, the Swiss bank PostFinance, PayPal, MasterCard, and Visa due their anti-WikiLeaks conduct. Both MasterCard's and Visa's websites were brought down on December 8.

During 2011 and 2012, an extraordinary number of attacks were recorded. The group of hacktivist was very active in 2011, in particular during the Arab Spring when it conducted numerous offensives against the governments of Tunisia and Egypt.

The most clamorous attack during 2011 was on HBGary Federal in response to the announcement by its chief security executive of the security, Aaron Barr, that he had had the Anonymous group successfully infiltrated. In retaliation, members of the collective hacked the HBGary Federal website, accessed the company's e-mail, dumping the content of 68,000 messages, erasing files, and taking down their phone system.

During 2012, the group of hacktivists focused its attention on policies of governments around the world, let's remember the #opJapan to protest against amendments to the copyright laws in Japan, #opChina to manifest dissent against Chinese censorship, and also #opRussia, #opIsrael, and #opNorthKorea against the respective governments of those countries.

2013 started with a series of attacks just after the Aaron Swartz suicide and in the successive months the U.S., North Korea, and Israel governments were hit by numerous attacks without sensational repercussions. Just in the last few months, the FBI claimed to have neutralized Anonymous thanks to a long series of arrests that hit principal cells of the collective, such as LulzSec, Antisec, and SABU. One of the FBI officials declared:

"All of these guys were major players in the Anonymous movement, and a lot of people looked to them just because of what they did … The movement is still there, and they're still yacking on Twitter and posting things, but you don't hear about these guys coming forward with those large breaches," he said. "It's just not happening, and that's because of the dismantlement of the largest players."

The FBI considers these arrests a "huge deterrent effect," according to Austin P. Berglas, the assistant special agent in charge of the bureau's cyber division in New York.

Hacktivism and policy

Today the contrast between governments and groups of hacktivists has reached the proportions of a cyber war; continuous offensives menace governments' infrastructures and sensitive data. To respond to the cyber threats, many states are spending a considerable effort on the tracking and the infiltration of groups like Anonymous.

The fight for freedom of expression, the defense of human rights, the total aversion to any form of surveillance and control, and the reporting of abuse by regimes are the main arguments that incite groups of hacktivists to action; however, the boundary between interpreting an operation as a simple act of protest or as a cybercrime is thin.

While most operations are limited to DDoS attacks against a few websites, often the disclosure of information obtained by hacking target systems has exposed sensitive data to the public with serious consequences.

Hacktivism surprised the IT security community, creating serious damage to both the private and public sectors. It was a great error to underestimate its cyber capabilities and the media impact of groups of hacktivists. Emerging collectives are considered as uncontrollable variables in cyberspace, able to undermine the delicate balance.

The strength of hacktivism is its capability to recruit large masses for its operation sharing through the democratic instruments of the Internet and social networks. Groups like Anonymous are able to involve new forces for each operation just by offering them the possibility to be part of a protest, a voice in a chorus that unites cries for vengeance. With the increase in initiatives taken by groups of hacktivists around the globe, governments, law enforcement, and intelligence agencies have understood the offensive potential of the phenomena and have tried to mitigate the threats by trying to infiltrate the collectives and increasing the surveillance on alleged participants in the protests.

Gen. Keith Alexander, current director of the National Security Agency, warned of the possible consequences of the attack organized by hacktivists against the national critical infrastructures such as a power supply.

Power supplies are just one possible target, together with telecommunications systems, gas and oil storage and transportation, banking and finance, transportation, water supply systems, and emergency services. The profile of cyber assaults against U.S. government and corporate targets is increasing, manifesting very complex cyber strategy.

"If forces like those of hacktivists have the technical capacities and critical mass such that they can influence foreign policy, are we sure that among their goals there are critical infrastructures?

Why we intend to define the components of Anonymous cyber-terrorists and cyber criminals?" said Gen. Alexander.

Hacktivism and cyber warfare

Is it really useful to decapitate the principal group of hacktivists or it is possible to exploit their operation for other purposes? Is it possible to incited state-sponsored attacks through groups like Anonymous?

Many governments recognized the benefit of infiltrating groups of hacktivists to influence the choice of the final targets for the cyber attacks. An attack could be exploited by a government to cover further offensives or simply to sabotage the enemy structures. Governments, involving a critical mass of people behind the group of hacktivists, could cover their operations and, although many security experts and intelligence analysts consider this approach impractical, the recent revelations of Anonymous members confirmed this practice. Essentially it is possible that governments could corrupt a leader of one of the most influential cells to incite the attacks against their adversary. Another approach is organizing fake cells of hacktivists that recruit ordinary people to organize cyber operations against hostile governments.

Groups like Anonymous have been driven by purely political motivations; a government influencing the strategies of a group of hacktivists could destabilize an opponent by exaggerating the tone of the internal political debate. The Arab Spring has taught the world how dangerous can be a wind of protest fueled through the new social media.

Recently former LulzSec leader Sabu (Hector Xavier Monsegur) was accused by the hacker Jeremy Hammond of having incited state -sponsored attack against the U.S. government.

LulzSec was a popular group of hacktivists that breached many high-profile targets, such as the Sony Pictures hack that occurred in 2011. The list of victims includes also notorious companies and intelligence agencies such as AT&T, Viacom, Disney, EMI, and NBC Universal, The Sun, The Times, and the CIA.

One of the LulzSec leaders, Hector Xavier Monsegur, aka "Sabu," when he was arrested started collaboration with law enforcement to track down other members of the Anonymous collective. The information provided by Sabu on the organization of his cell allowed law enforcement to arrest other members of Anonymous.

Figure 3. Sabu, leader of Lulzsec group

Another member of Lulzsec, the hacker Jeremy Hammond, maintains that the FBI used Sabu to coordinate attacks against foreign governments. Hammond pleaded guilty in May for the data breach of the private intelligence firm Stratfor and he is waiting for his sentence, scheduled for November 15, 2013, he faces up to 10 years in prison. According to Hammond, the FBI has exploited the capabilities of Sabu to influence large masses to support Lulzsec during attacks against targets of the U.S. Government. The recruitment of leaders of a group of hacktivists has numerous advantages: First of all, there is no official liability for the attacks and the opportunity to exploit campaign if hacktivists hides more sophisticated attacks conducted by government cyber units.

Not negligible is the fact that this kind of operation has a limited cost compared to a state-sponsored attack. The infiltration of group of hacktivist is a strategic tactic for any government, as remarked by Jeremy Hammond, who publicly accused Sabu in a blog post:

"I write this in advance of the sentence of Hector Monsegur, aka 'Sabu'—a former Anonymous comrade turned FBI informant—scheduled to take place on August 23, 2013. It is widely known that Sabu was used to build cases against a number of hackers, including myself. What many do not know is that Sabu was also used by his handlers to facilitate the hacking of targets of the government's choosing – including numerous websites belonging to foreign governments. What the United States could not accomplish legally, it used Sabu, and by extension, me and my co-defendants, to accomplish illegally. The questions that should be asked today go way beyond what an appropriate sentence for Sabu might be: Why was the United States using us to infiltrate the private networks of foreign governments? What are they doing with the information we stole? And will anyone in our government ever be held accountable for these crimes?"

Once it has infiltrated a collective through its leaders, the intelligence agency can interfere with the choice of targets and could raise debates on specific topics to modify the sentiment of the population of a foreign country.

Surely this abuse of hacktivist movements has been a long debated by intelligence agencies and what Hammond described is probably a consolidated practice. The principal risk of infiltrating of group of hacktivists is the unstable organization of the interlocutors.

In the arsenal of hacktivists

Let's start from the simple assumption that hacktivists do not necessarily have high computer skills; exactly as in any other organization it is possible to recognize high-tech profiles, distinguishing them from entities involved in the evolution of the movement. A hacktivist is not necessarily a member of a group. In most cases he is a youngster that decided to take part in a social protest.

The principal expression of dissent manifested by a group of hacktivist is the DDoS attack: This method is most popular within the hacktivism ideology world due to its efficiency and the simplicity of arranging offensives.

In most cases, execution of DDoS attacks does not need the knowledge of vulnerabilities to exploit the target application. Imperva released its September "Hacker Intelligence Report," a document that confirmed the adoption of DDoS attacks for politically motivated attacks.

"Denial of service is a primitive, yet popular attack vector for politically and profit-motivated hackers … DDoS can gridlock enterprise resources to a halt, just like traffic on the highway, but organizations can mitigate these effects by learning how to identify and protect against malicious traffic." said Imperva's senior web researcher, Tal Be'ery.

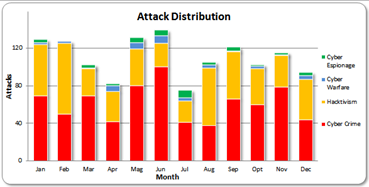

In the arsenal of hacktivists, the primary weapons are DDoS tools and vulnerability scanners. Most of the applications used by hacktivists are easily found on the Internet in hacking forums and on the black market. On IRC channels and websites such as Pastebin, it is possible to find references to the tools and also mini-guides for their use.

Figure 4. DDoS tools list (Pastebin)

Among the most popular tools used by groups of hacktivists there are LOIC, Slowhttp, PyLoris, Dirt Jumper, Nuclear DDoSer, High Orbit Ion Cannon (H.O.I.C.), Torshammer, Qslowloris, etc.

LOIC

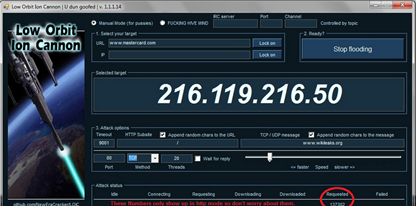

LOIC is an open source network stress testing tool that can be used for a denial-of-service attack. It was initially developed by Praetox Technologies, but its code was later released into the wild, giving the possibility for various teams of developers to personalize it according their needs. An example is the web version called Low Orbit Web Cannon, which is usable directly from a web browser

Essentially the tools stress the targets by launching HTTP POST and GET requests. Its use is very simple: The attacker just needs to know the target IP address. LOIC was adopted for the first time by members of Anonymous during the campaign Project Chanology against Scientology and during Operation Payback.

Figure 5. LOIC screenshot

Mobile LOIC

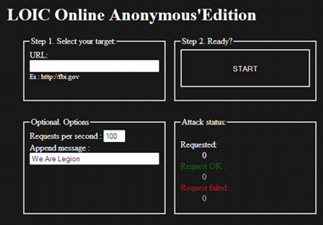

Mobile LOIC is the extension of the popular tool for the mobile environment. The DoS is conducted by simply browsing to a web page containing the attack code. The attacking code is written in JavaScript and it is usually automatically downloaded to the user's browser. The JavaScript-based HTTP DoS tool iterates endlessly created multiple requests to the target; as long as the page opens, the browser continues to send the requests. Unlike the traditional LOIC, it doesn't require downloading of any application, and it can run on various browsers including a mobile version for smartphones.

Mobile LOIC has very few options and is limited to conducting HTTP floods. It does not support more advanced features such as remote control by IRC botnets ("the Hive").

Mobile LOIC has only three configuration parameters:

- Target URL—the URL of the attacked target.

- Requests per second—the number of desired requests to be sent per second

- Append message—the content of the message parameter to be sent within the URL of HTTP requests; typically it is a proclamation from the group of hackers.

As revealed by security experts at Radwar, a new variant of the Mobile LOIC was detected that incorporates several techniques to bypass detection and provide greater redundancy. These include:

- A JavaScript method that prevents left mouse click in order to prevent users from viewing the page source code.

- Obfuscating all JavaScript methods contained and referenced on the page, which may slow down security researchers from fully investigating this tool and its capabilities.

- Removal of a message field that existed in the original version and had its value included in the attack packets themselves. This is most likely in order to try and avoid signature-based protections.

- Links from each attack page to up to four mirror attack pages hosted on other servers in order to quickly reference users and allow the attack campaign to continue even if one or more of the mobile LOIC nodes are taken down.

- In addition, several "cosmetic" functionalities were added, such as listing the number of current attackers using the tool, and reflecting the current client IP detected by the tool, which may prove useful when trying to avoid attacks using an attacker's real IP address.

Figure 6. Mobile LOIC

Use of the tool was documented by the Imperva security firm in various Anonymous campaigns such as OpColombia, OpRussia, and OpBahrain.

Figure 7. Mobile LOIC used for OpRussia (Imperva)

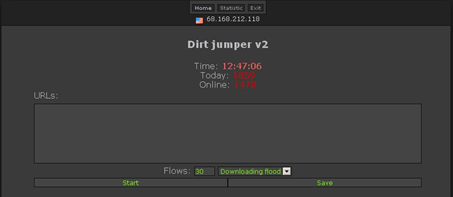

Dirt jumper

Dirt Jumper is a collection of DoS tools. More than five versions of Dirt Jumper are available online for free. In the underground, it is possible to find numerous versions of the tool that include more features than the basic configuration. Principal derivations are Di-BoTNet, RussKill, and Pandora DDoS. According to the Pandora creators, 1000 bots are enough to bring down a giant portal such as the Russian search engine Yandex.

Figure 8. Dirt jumper

PyLoris

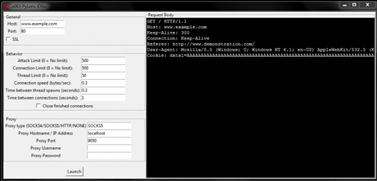

This is a multiplatform, Python-based tool that saturates the victim's resources by opening connections that it never closes. PyLoris is based on the Slowloris DoS technique. It is able to create a large number of full TCP connections and keep them open so the target will soon reach the maximum number of maintained connections.

PyLoris is ideal to target any web service that can manage a limited number of simultaneous TCP connections, but all those services that handle connections in independent threads/processes but with poor management for a pool of connections could be easily saturated with this tool.

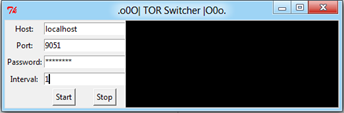

Very interesting is the TOR Switcher feature that allows the attackers to carry out an offensive over the Tor Network to anonymize the real source of the attack. The attacker could also switch between Tor "identities" to deceive defense systems.

Figure 9. PyLoris

Figure 10 - PyLoris Tor Switcher Feature

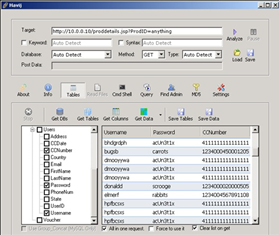

Not Only DDoS – Havij & Google Dorks

Up until now, we have exclusively analyzed tools used by groups of hacktivists for DDoS attacks. They are very popular for the reasons mentioned, but many members of groups like Anonymous have great cyber capabilities. In many cases these individuals with a high profile have a primary role in the black market, and they often propose DIY (do it yourself) tools to the underground community. One of the most popular tools used by hacktivists is Havij, an SQL injection tool that automates the search and exploit for SQL injection vulnerabilities into web services. Havij is considered one of the most efficient injection tools, with a very high success rate at attacking vulnerable targets.

Figure 11. Havij GUI

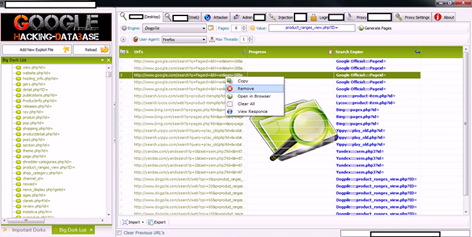

There are also other interesting tools for SQL injection. The most popular are Sqlninja, Safe3SI, and Sqlmap. Another powerful instrument in the hand of hackers and often used by hacktivists is Google Dorks; in particular, various hacking forums propose numerous DIY Google Dorks-based hacking tools that allow the automization of all queries used by hackers in various phases of their attacks.

Figure 12. DIY Google Dorks tool

Other techniques used to compromise websites are:

- Use of search engine reconnaissance through DIY SQL/RFI (remote file inclusion) tools or botnets; the category includes a wide range of application that automatically exploit improperly configured websites, such as blogging platforms or well known CMS.

- By using mined data or stolen accounting data, cyber criminals could gather information on malware-infected machines, looking for login credentials to be automatically abused with malicious scripts, and an actual executable being hosted on legitimate websites in an attempt to trick a security solution's IP reputation process.

Conclusions

Considering the hacktivists as pure criminals is an error, in my opinion. These individuals are not motivated purely by profit. Their operations have never sabotaged critical infrastructures nor have they disrupted critical systems, inflicting physical damage.

Anonymous, in an official message sent to the Wall Street Journal, dismissed the accusation that it is only a group of criminals with the following statements:

"Ridiculous! Why should Anonymous shut off power grid? Makes no sense! They just want to make you feel afraid."

However, I do consider the operations of groups of hacktivists a serious menace for private businesses and governments and I thing that, to mitigate their action it is essential to distinguish their means and methods from pure cybercrime activities. The two categories could share tools and hacking techniques but are two completely different phenomena. The concrete risk, in my opinion, is the fact that governments could misuse popularity of these groups for PSYOPs.

Despite the numerous arrests of hacktivists made by law enforcement worldwide, I don't consider the energy of these movements exhausted. They are mutating, but groups like Anonymous continue to attract talented hackers. Technology is an essential component of our society. Cyberspace and reality are even more overlapped and it is normal that a growing number of individuals will exploit their cyber capabilities to express their dissent. We must not let our guard down in periods of relative calm like this.

Get your guide to the top-paying certifications

With more than 448,000 U.S. cybersecurity job openings annually, get answers to all your cybersecurity salary questions with our free ebook!

Sources

- Cyber crime - Security affairs

- Denial of Service attacks trends, techniques and technologies - Imperva

- FBI claims neutralized anonymous - Security affairs

- Hacking new Diy Google Dorks - Security affairs

- Sabu incited state sponsored attack - Security affairs

- 2012 Cyber attacks statistics

- Knowledge center

- Anonymous Lulz collective action

- Verizon enterprises archives

- Now anyone can hack a website thanks to clever free programs

- Anonymous could become a cyber weapon - Security affairs